In Chapter 11, I learned about testing my code. Testing is an important part of programming as it ensures that code is working correctly. I can even test new code as I add it to make sure changes do not break my program’s existing behavior. Code must be tested often to catch any errors before users encounter them.

Throughout the chapter I used pytest, a library that helps write tests quickly and simply while supporting the tests as they grew in complexity along with their corresponding projects. The pytest library is considered to be a third-party package, a library that is developed outside the core Python language.

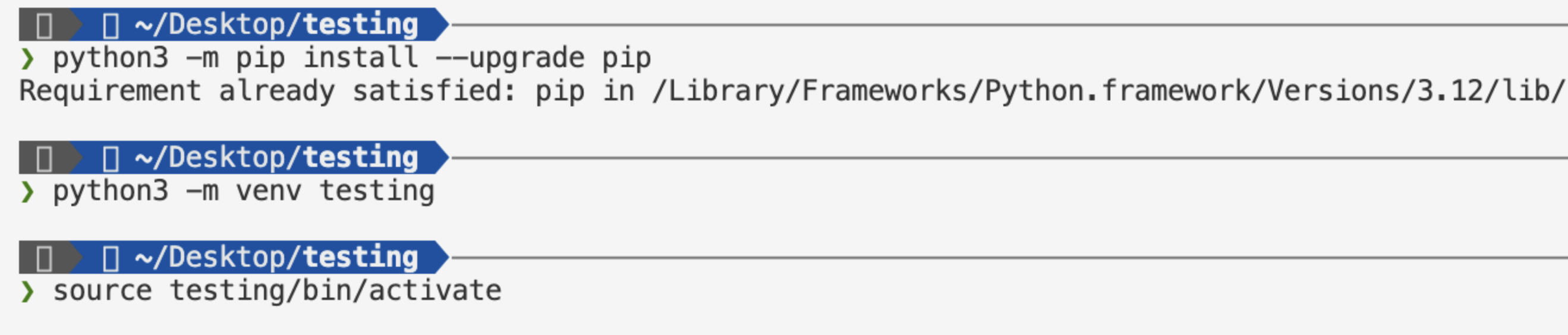

I started by upgrading pip, a tool used to install third-party packages. Because pip helps install packages from external resources, it’s updated often to address any potential security issues.

It’s best practice to use virtual environments when starting a Python project. A virtual environment isolates project dependencies, preventing conflicts with other projects on my system. The first line python3 -m venv testing installs a virtual environment with the name testing. The second line source testing/bin/activate activates the virtual environment.

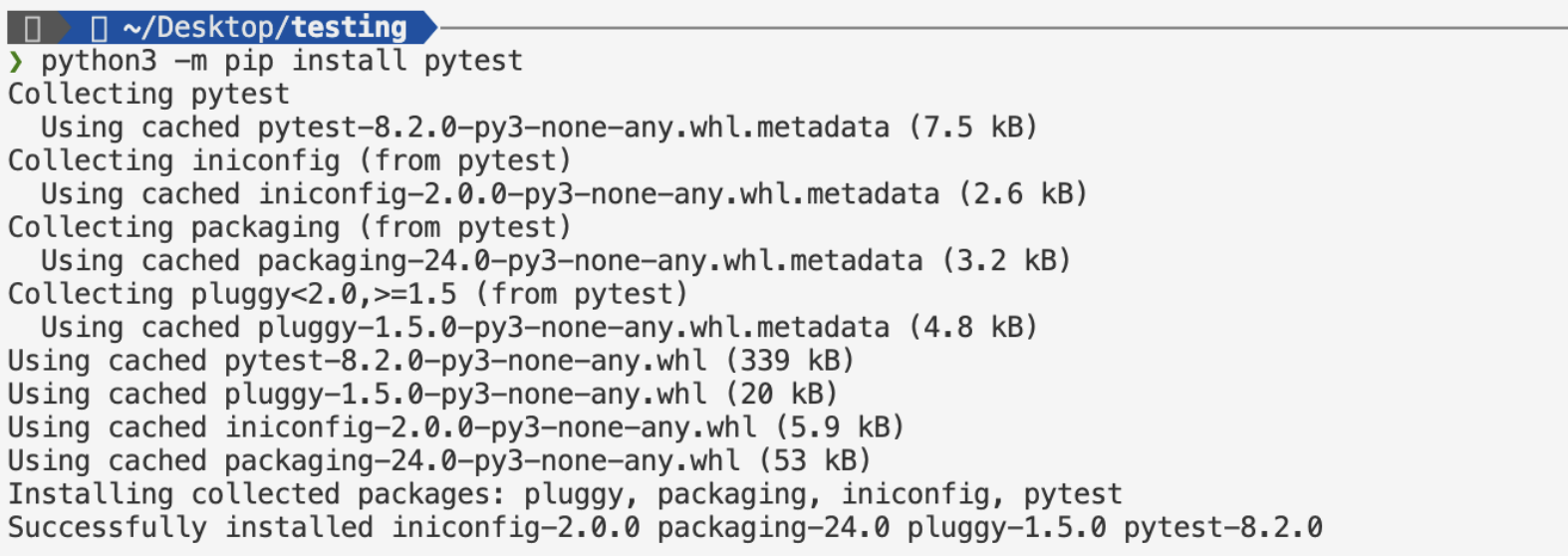

After installing the virtual environment, I successfully installed pytest.

Testing a Function

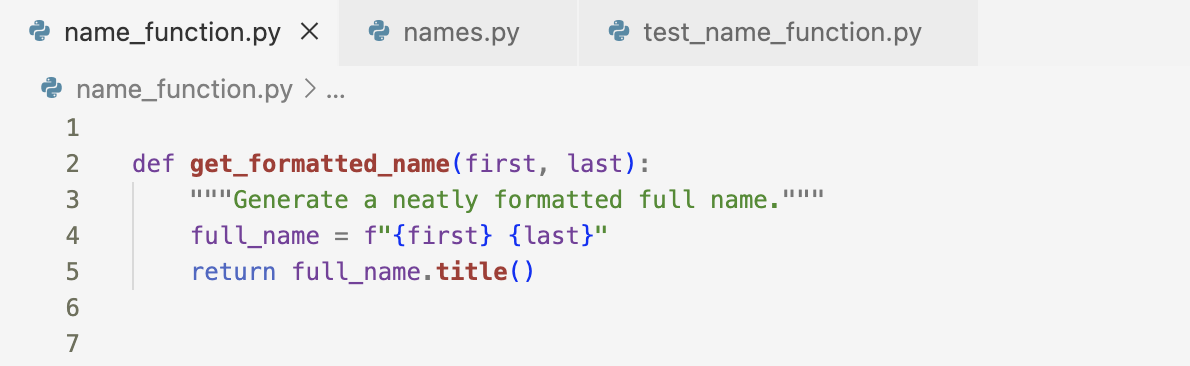

Below I created the name_function.py file that combines the first and last name with a space to make a full name, then capitalizes and return the full name.

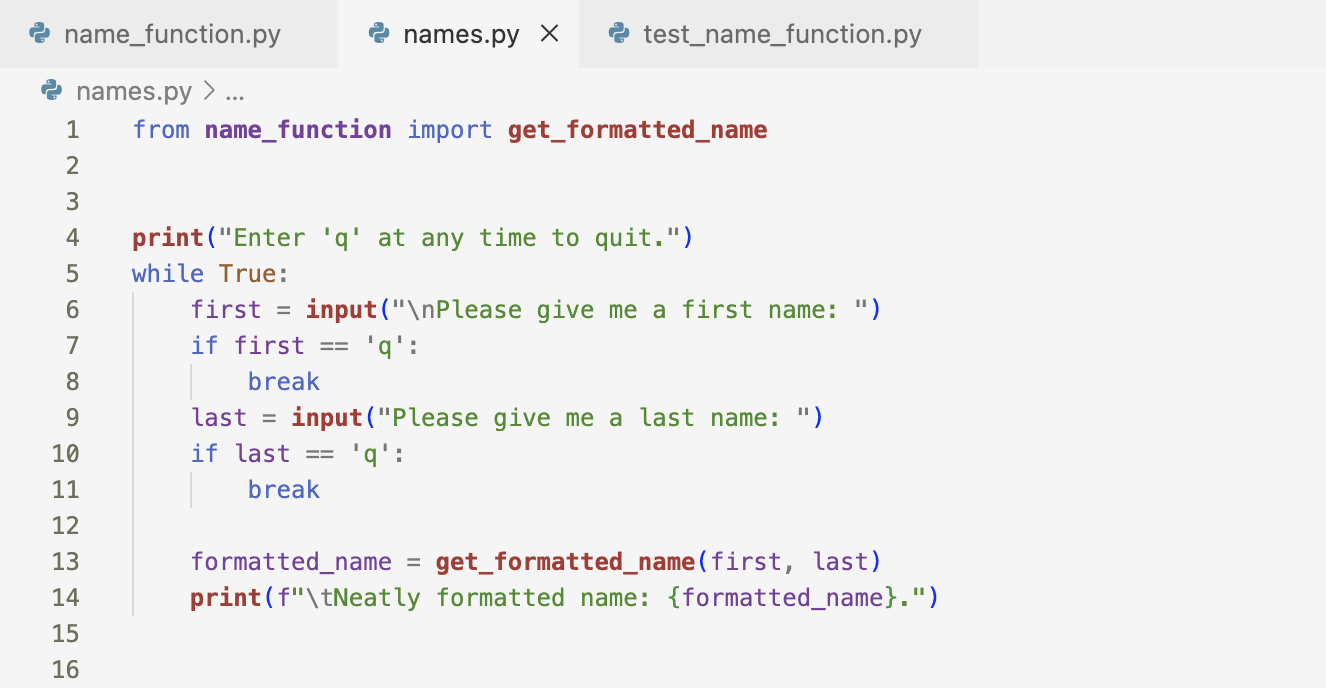

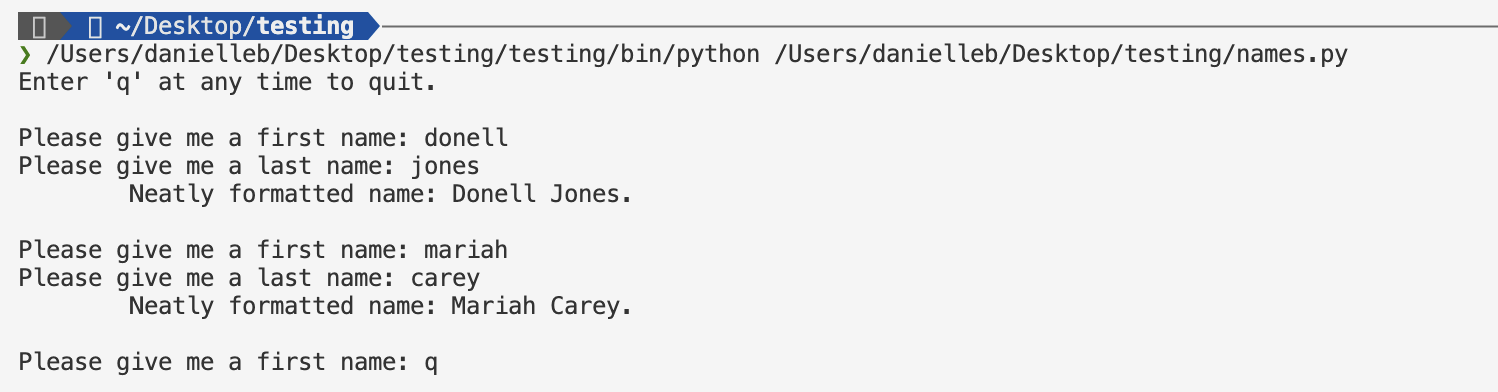

I created the names.py file which imports get_formatted_name() from name_function.py. This program checks that the get_formatted_name() function works correctly.

The user can enter a series of first and last names and see the formatted full names.

I could continue to test this code by running names.py and entering a name like Donell Jones everytime the get_formatted_name() function is changed but that is tedious work.

This is where pytest comes in. It provides an efficient way to automate testing of a function’s output.

Before I jump into testing there are a few concepts about unit tests and test cases I need to understand.

Unit tests are some of the most basic building blocks of software testing. Each unit test focuses on checking a single, specific part of a function’s functionality. By combining multiple unit tests into a test case, we can verify that the entire function behaves as expected across all the scenarios we anticipate it might encounter. Ideally, a well-designed test case considers every possible input the function could be given and includes a specific unit test to represent each situation. To achieve full coverage, a test case should include a comprehensive set of unit tests that explore all the different ways the function can be used.

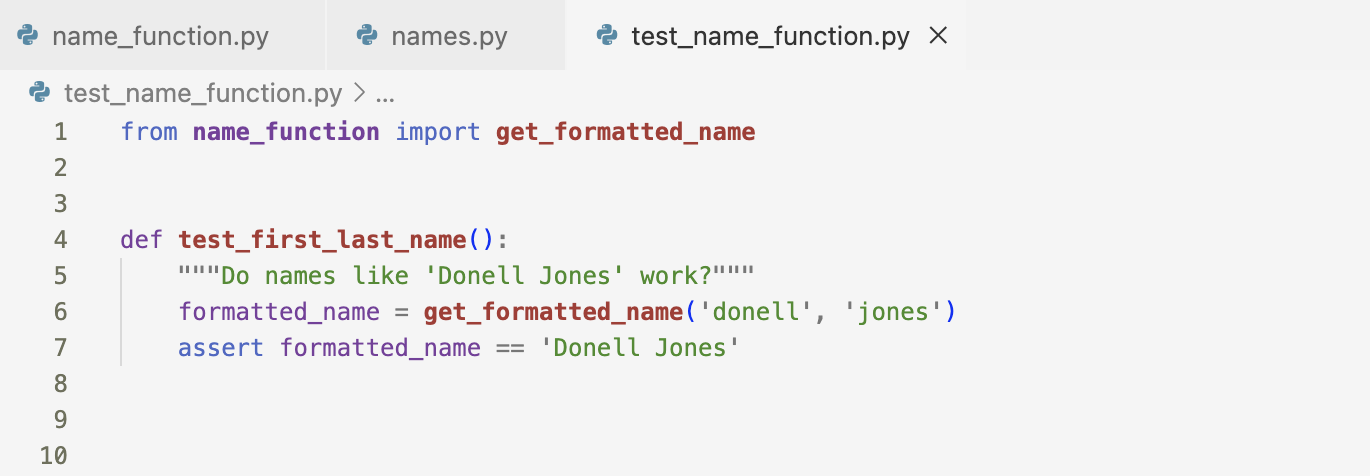

Creating my first unit test with pytest was pretty simple. I created a test file called test_name_function.py. A test file must start with the word test followed by an underscore. I imported the name_function file into my test_name_function.py file. I then created the function test_first_last_name.

Test functions also need to start with the word test followed by an underscore. This is so that the test will be discovered by pytest and run as part of the testing process. Test names should be longer and more descriptive that the typical function name so that if I see the function name in a test report, I’ll have good sense of what behavior is being tested.

I call the function that’s being tested with my arguments, ‘donell’ and ‘jones’. I assign this return value to formatted_name.

Finally, I make an assertion, a claim about a condition. So formatted_name should be ‘Donell Jones’.

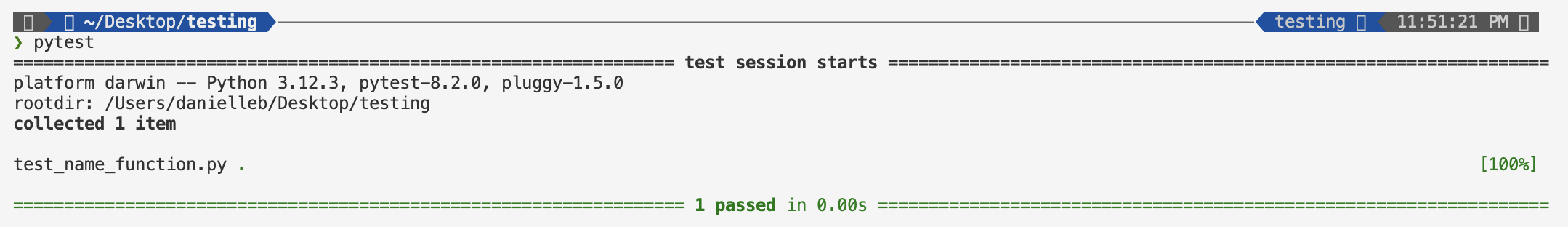

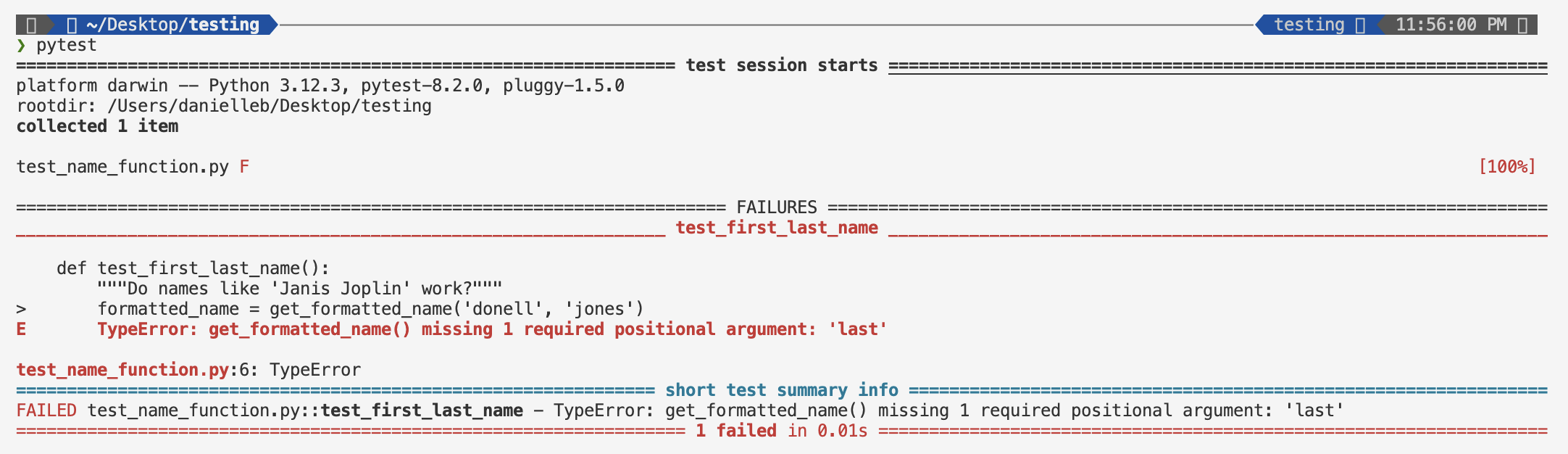

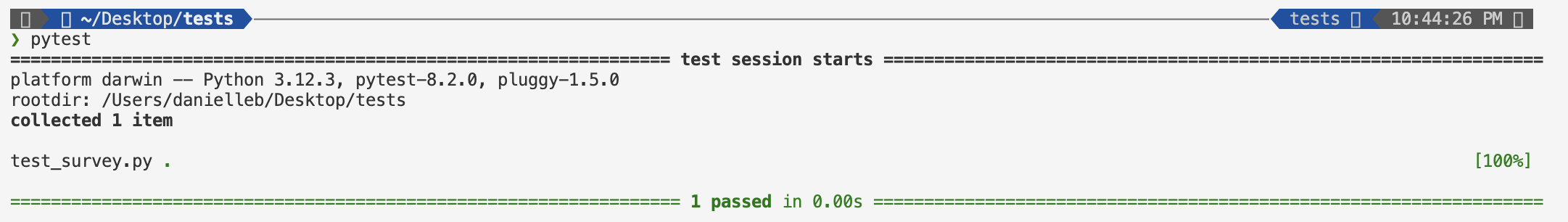

Instead of running my test_name_function file directly, I entered the command pytest in the terminal window.

The output contained information about the system the test is running on. In my case, I tested this on a macOS. I also saw which versions of Python, pytest, and other packages are being used to run the test. I saw the directory where the test was being ran from and the test file that was ran. The single dot after the test file let me know that my single test passed and the 100% means that all the tests were run. The last line told me that the one test passed and that it took 0.01 seconds to run the test.

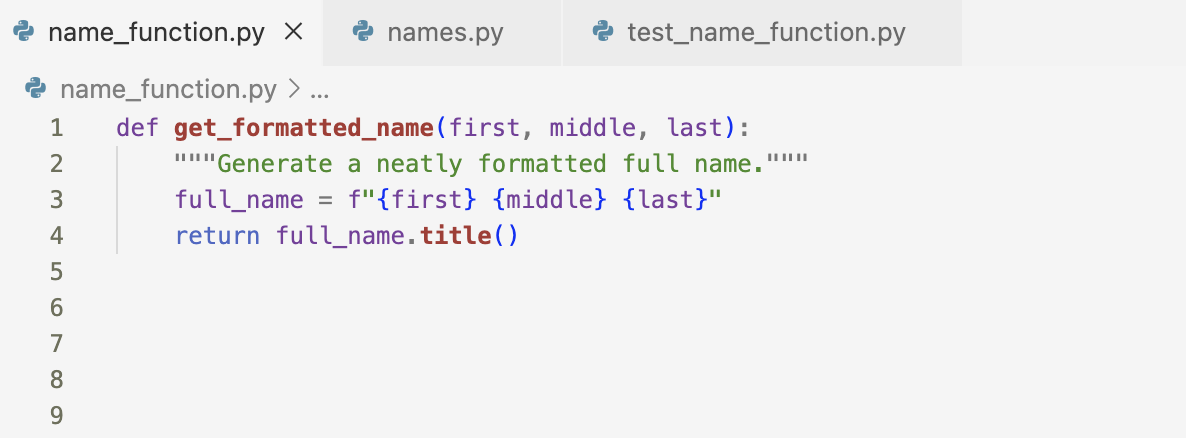

Now let’s see what happens when I add a middle name to the get_formatted_name function.

Once I again, I entered the pytest command. However, this time my test has failed. The single F next to the filename indicated that one test failed. There is a FAILURES section that details why the test failed. It highlights that the test_first_last_name function was the test function that failed. An angle bracket indicates the line that caused the code to fail. The E shows the actual error that caused the failure: A TypeError due to a missing positional argument, last. The most important information is repeated in the short test summary info section.

So how do I go about responding to this failed test?

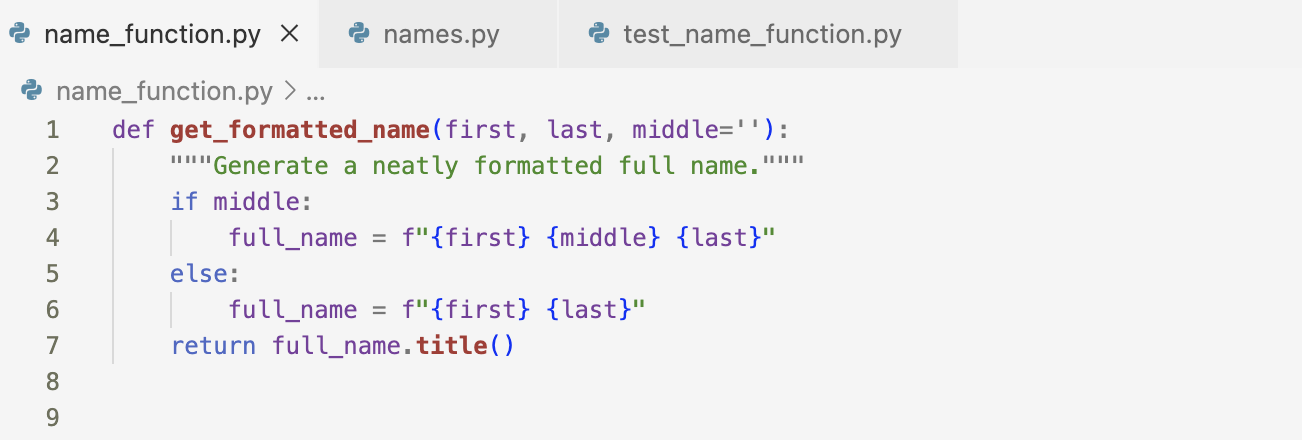

If a test fails, I do not go and change the test. If I do, any code that calls my function like the test does will stop working. Instead, I fix the code that caused my test to fail.

To fix this code, I decide to make the middle name optional. I moved the middle parameter to the end of the parameter list in the function definition and give it an empty default value. I added an if test that builds the full name depending on whether a middle name is provided.

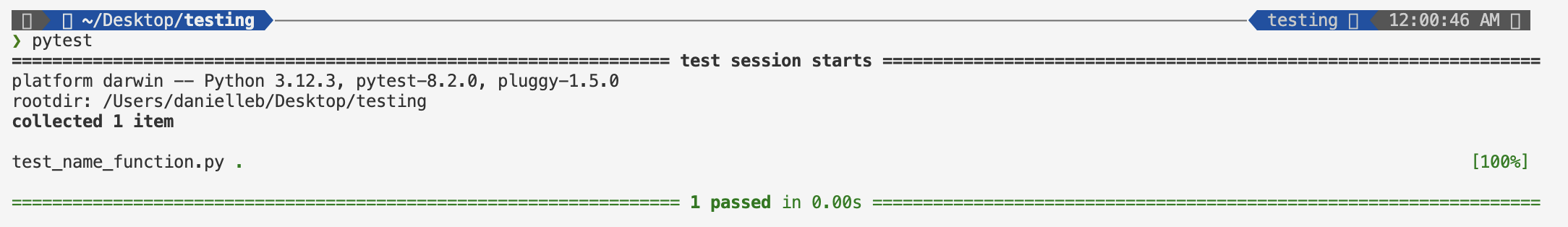

When I made these changes, the test passed.

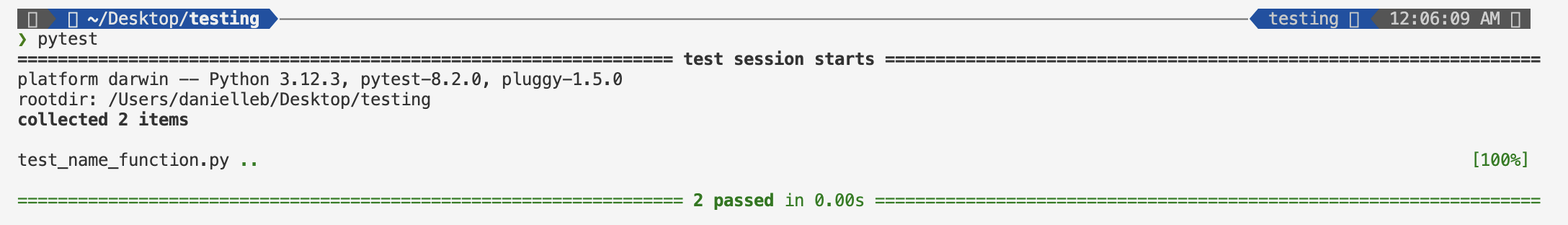

I added a second test function for people who include a middle name. I named this new function test_first_last_middle_name. I call get_formatted_name with a first, last, and middle name. Lastly, I make an assertion that the returned full name matches the full name I expect.

I ran pytest and both tests passed. The two dots indicate that two tests passed, which also made clear by the last line of output.

Testing a Class

Testing a class is similar to testing a function because much of the work is testing the behavior of the methods in that class. However, there are a few differences.

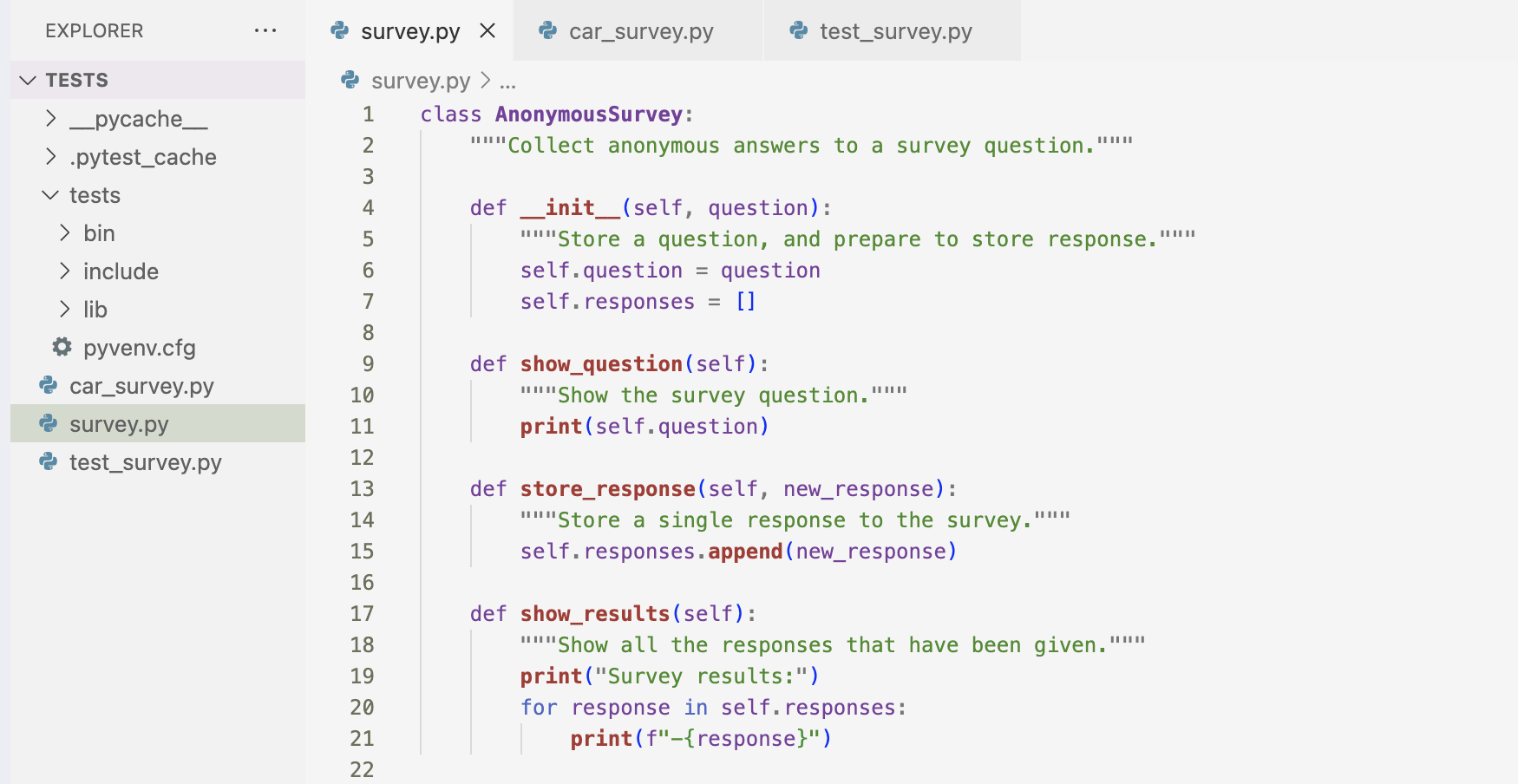

Using the example from the book, I wrote a class that helps administer anonymous surveys.

The class starts with a survey question that I will provide and includes an empty list to store responses. It has methods to print the survey question, add a new response to the response list, and print all the responses stored in the list. To create an instance from this class, all I have to provide is the question.

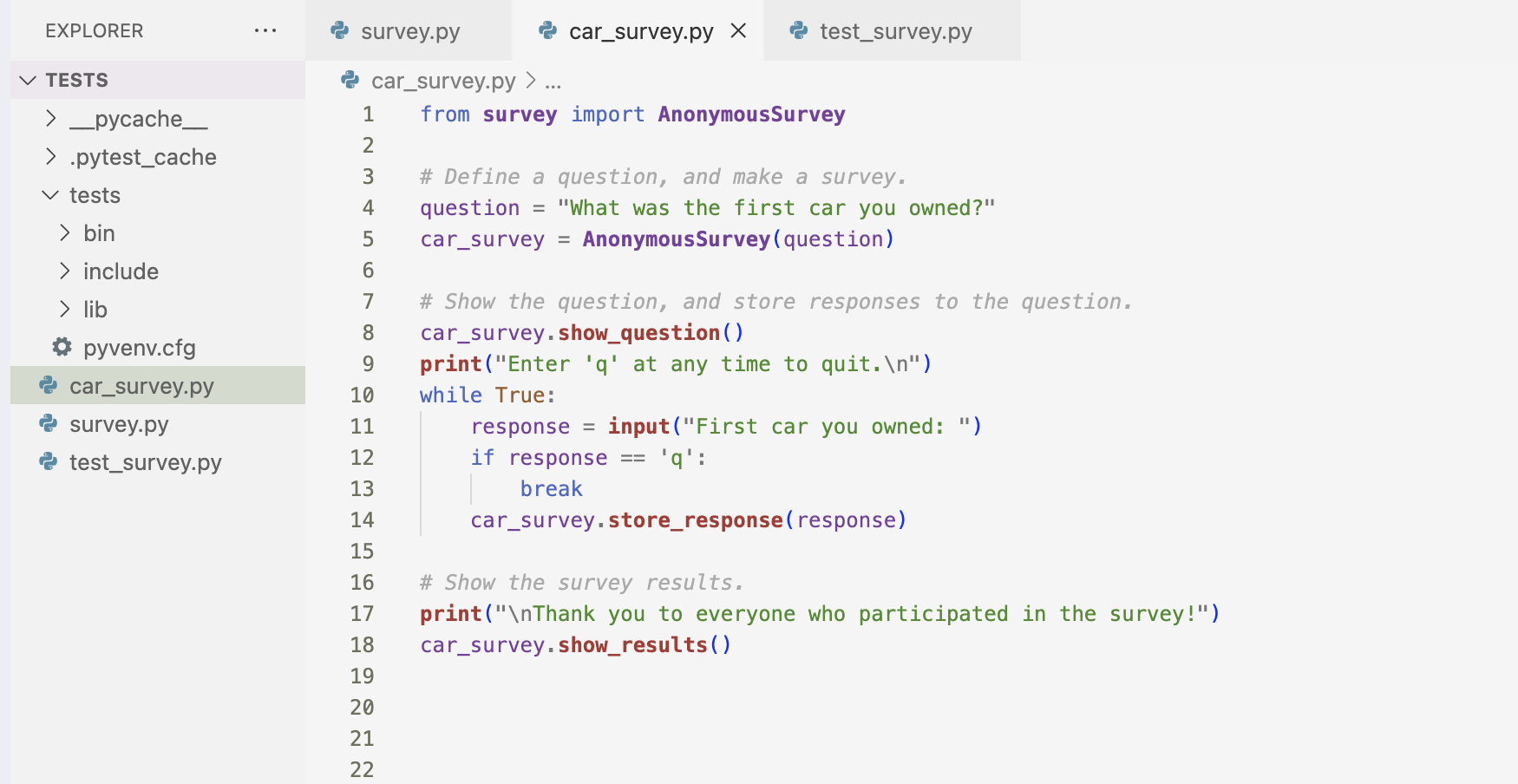

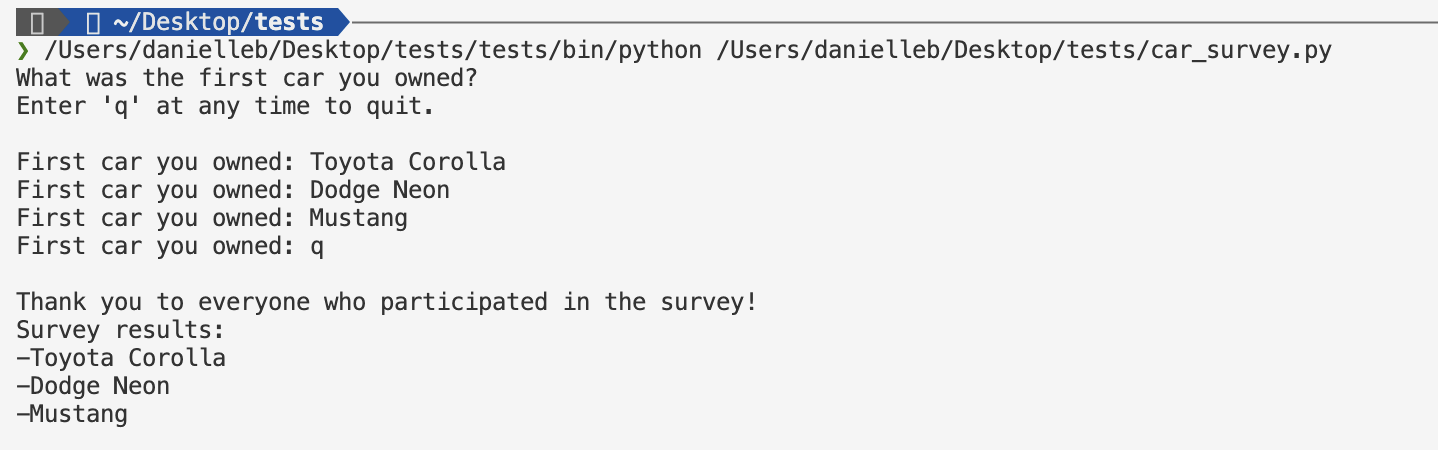

I wrote a program to show that the AnonymousSurvey class works. I asked the user my question and create an AnonymousSurvey object with that question. The program calls show_function() to display the question and then prompts for responses. Each response is stored.

When all the responses are stored (the user enter ‘q’ to quit), show_results() prints the survey results.

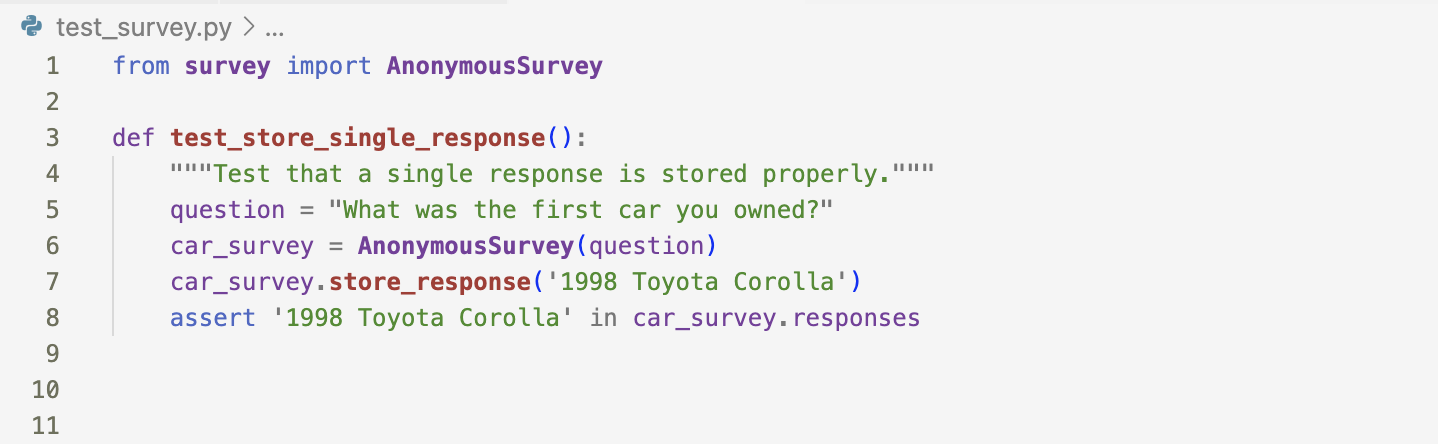

Now I test the AnonymousSurvey class. Now surveys are only useful when they generate more than one response. So I tested for a single response and multiple responses.

First, I tested the class to verify that a single response is stored correctly.

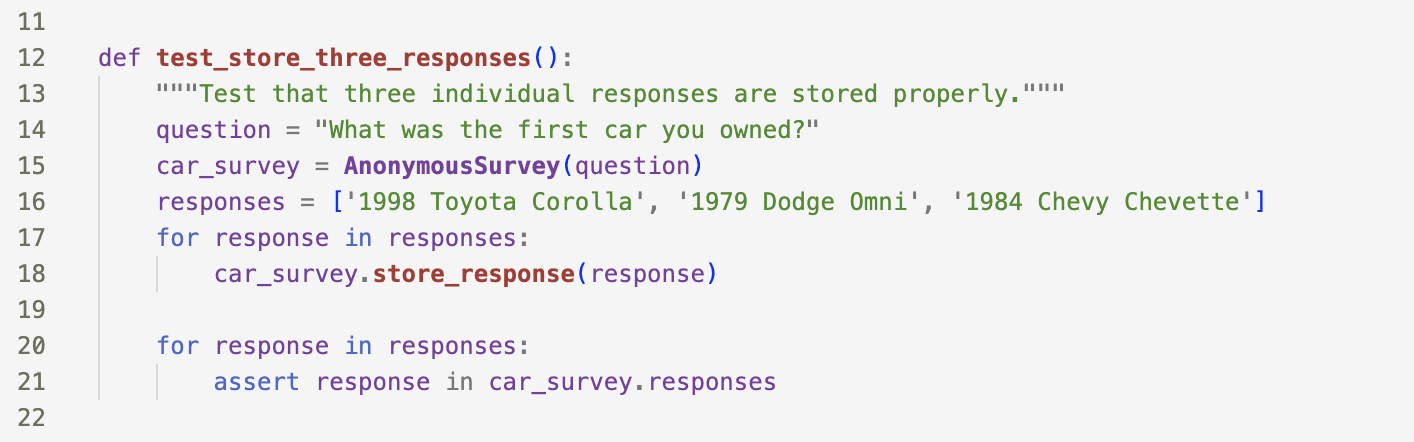

Then I tested the class again to verify that multiple responses are stored correctly. I created a new function test_store_three_responses. I created a survey object, then defined a list containing three responses. I called store_response() for each response. Once the responses have been stored, I write another loop to assert the each response is in car_survey.responses.

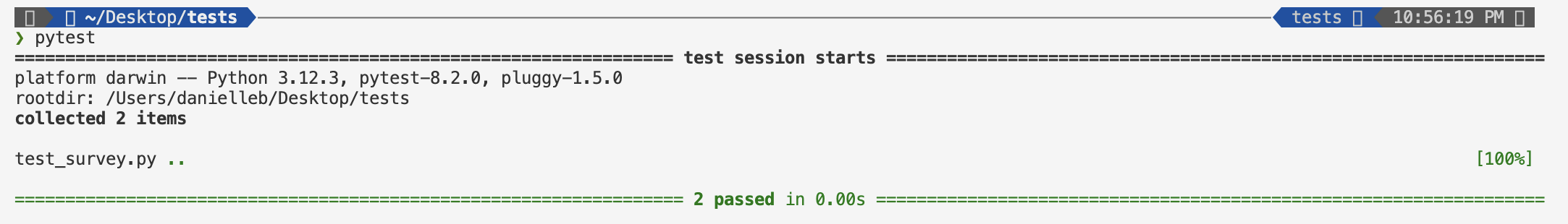

I ran the test file again and both tests passed.

Fixtures

In my test_survey.py file, I created a new instance of AnonymousSurvey in each test function. While this works for a simple test it will not work in a real-world project where there are possible hundreds of tests.

In my testing process, I might need a reusable element across multiple tests. Pytest lets me create such elements using fixtures. Fixtures help set up tests environments. These fixtures are defined as functions decorated with @pytest.fixture. Decorators in Python are special functions that modify the behavior of the functions they’re attached to. In this case, the @pytest.fixture decorator tells pytest to handle the function in a specific way, making it reusable for your tests.

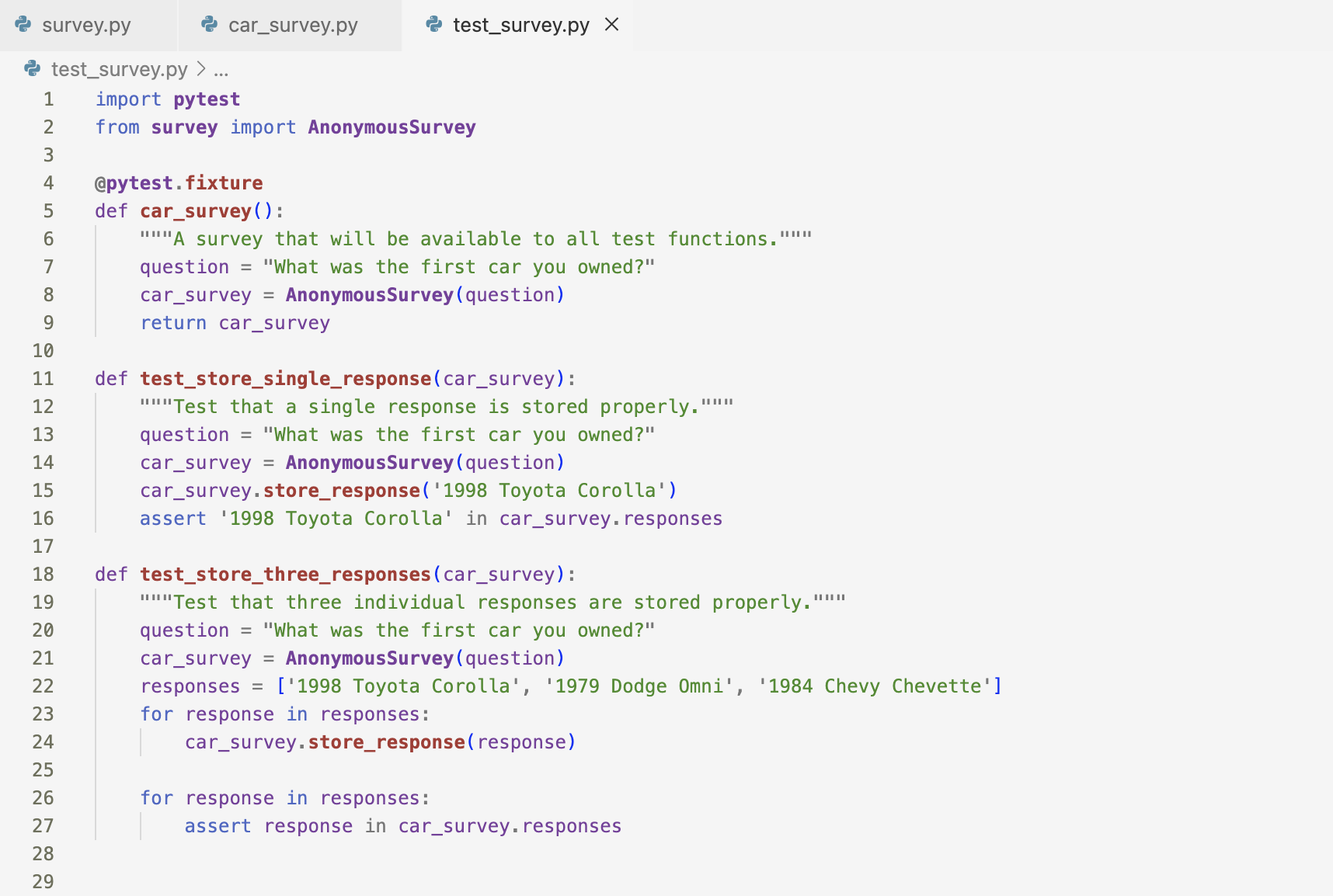

I used a fixture to create a single survey instance that can be used in both test functions in test_survey.py

I’ll need to import it because we’re using a special function, called a decorator, provided by pytest. This decorator, @pytest.fixture, is applied to a new function named car_survey(). This function creates a new AnonymousSurvey object and returns it.

Each test function now has a new parameter named car_survey. When a test function’s parameter matches the name of a function decorated with @pytest.fixture, pytest automatically runs that function (the fixture) and provides the return value to the test. In this case, car_survey() supplies both test_store_single_response() and test_store_three_responses() with a ready-made car_survey object.

However, I noticed that two lines have been removed from each test: the ones defining the question and creating the AnonymousSurvey object.

What if I decide to run both tests again? Both tests will still pass. These tests become especially valuable when I modify AnonymousSurvey to handle multiple responses per person. By running these tests after making changes, I can ensure that the ability to store single and multiple responses remains intact.

Going through the first part of Python Crash Course has been an amazing experience! I became reacquainted with concepts I knew and learned a few that were brand new to me. From here, I’ll begin to build projects. I am super excited about it and I can’t wait to post them on this site.