In Chapter 10, I learned about handling errors, exceptions, and working with files and data.

To work with contents in a file, I need to tell Python the path to the file. A path is the exact location of a file or folder on a system. Python provides a module called pathlib that makes it easier to work with files and directories. A module that provides specific functionality is called a library.

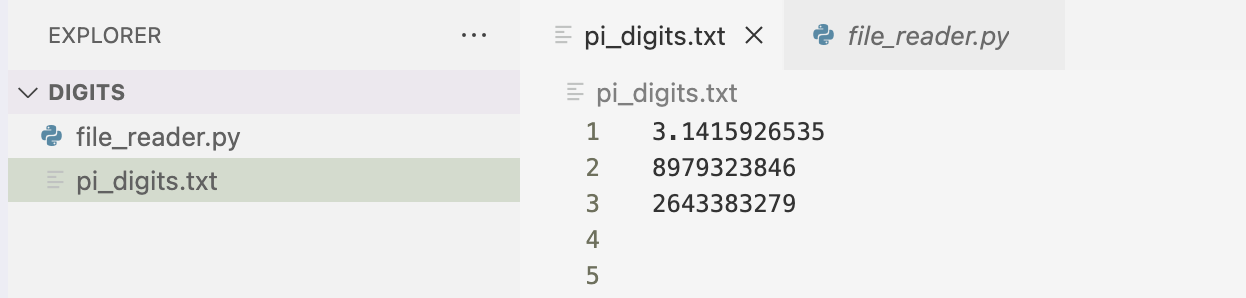

Using the example from the book, I created a pi_digits.txt file that contains pi to 30 decimal places.

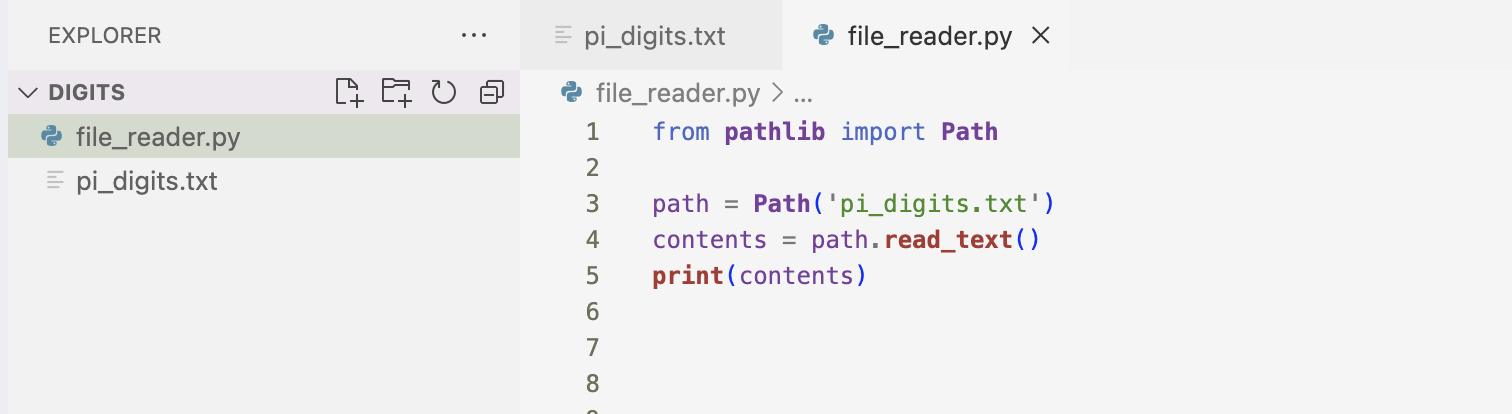

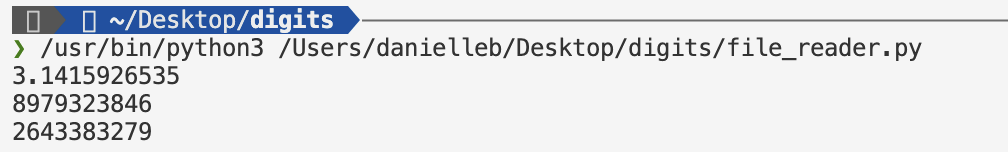

I then created a file_reader.py file that imports the Path class from pathlib. I build a Path object representing the text file that I assign to the variable path. Since the text file is saved in the same directory as the .py file I wrote, the filename is all that is needed for Path to access the file. I use the read_text() method to read the entire contents of the file. The contents are returned as a single string which I assigned to contents. I then print the value of contents.

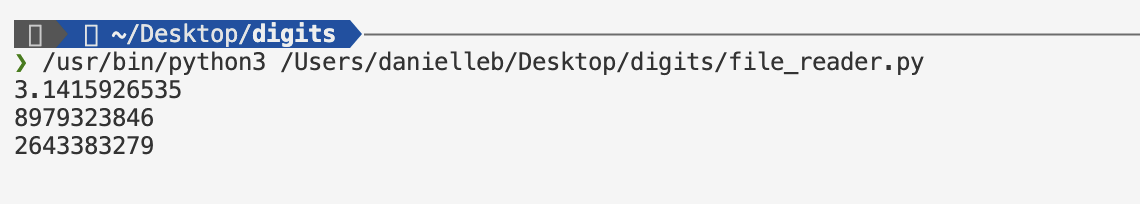

This is the result of printing the value of contents. I see the entire contents of the file.

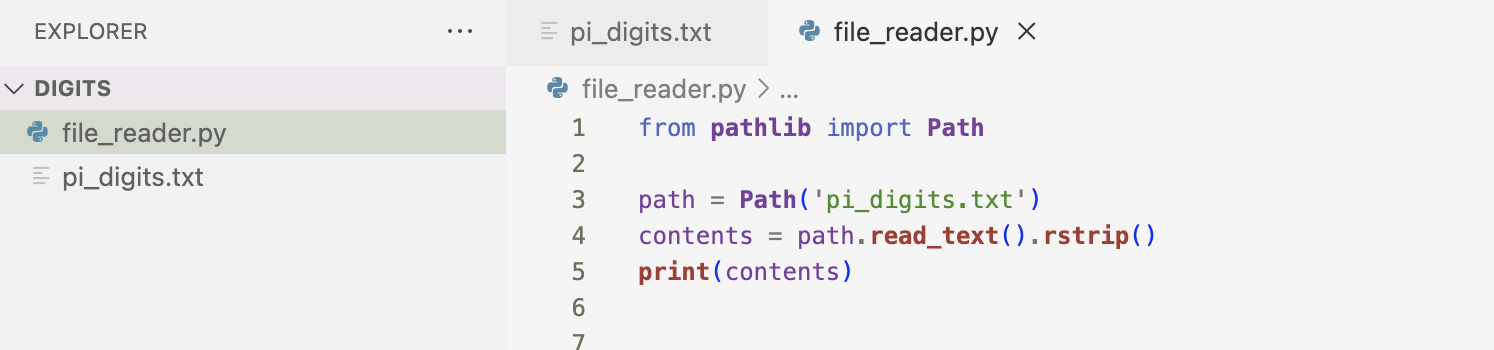

At the end of the output I notice that there is a blank line. This is because read_text() returns an empty string when it reaches the end of the output. To fix this, I use the rstrip() method on the contents string.

Now when I print the contents, the whitespace is removed from the output.

Relative and Absolute File Paths

There are times where the file I want to open will not be in the same directory as my program file. I would need to provide the correct path to get Python to open files from a directory other than the one where my program file is stored.

The are two ways to specify paths in programming.

A relative file path tells Python to look for a given location relative to the directory where the currently running program file is stored.

path = Path('text_files/filename.txt')An absolute file path tells Python exactly where the file is on your computer, regardless of where the program that is being executed is stored. Absolute paths are longer than relative paths because they start at your system’s root folder. I can read file from any location on my system using absolute paths.

path = Path('/home/danielle/data_files/text_files/filename.txt')If I wanted to access a file’s lines, I could use the splitlines() method to turn a long string into a set of lines and use a for loop to examine each line in the file, one at a time. Using the book example again, it would look like the code below. The output would be the same as above.

from pathlib import Path

path = Path('pi_digits.txt')

contents = path.read_text().rstrip()

lines = contents.splitlines()

for line in lines:

print(line)Now, I’m going to start working with my file’s contents.

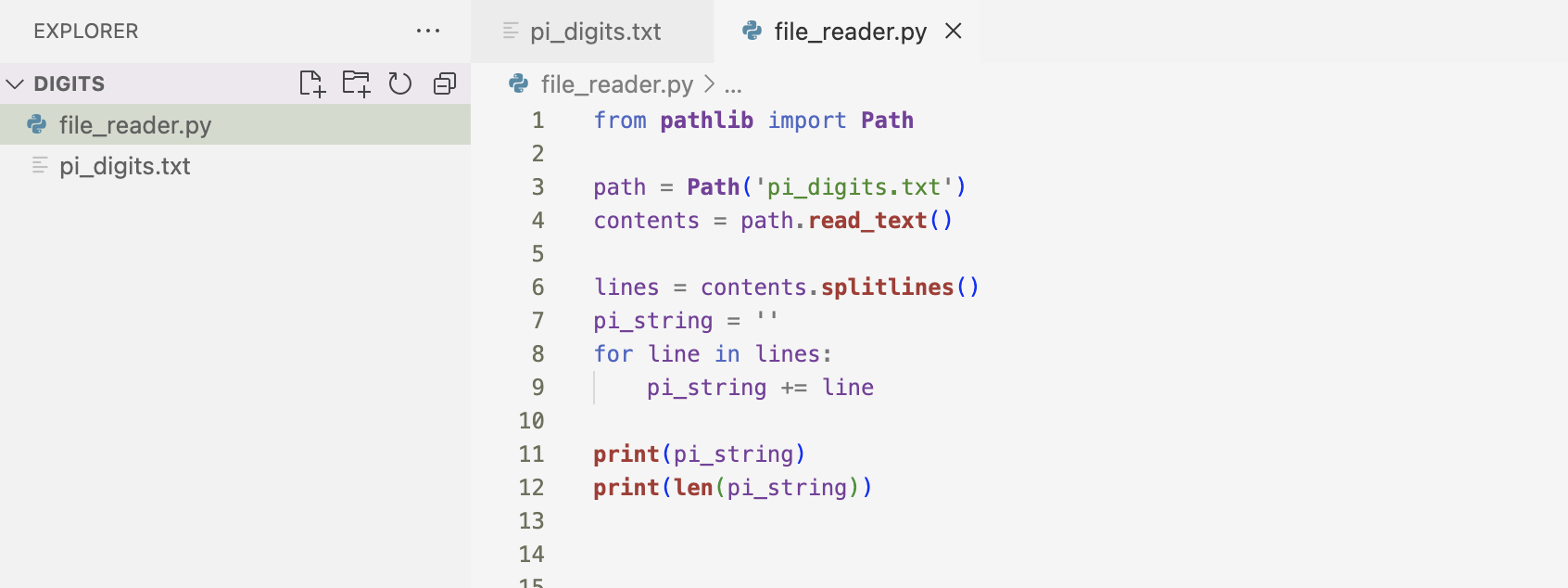

First, I created a single string containing the digits of pi. I built on the previous example by creating a variable, pi_string that holds the digits of pi. I used a for loop to add each line of digits to pi_string. I use the len() method to show how long the string is.

The output of the code is shown below.

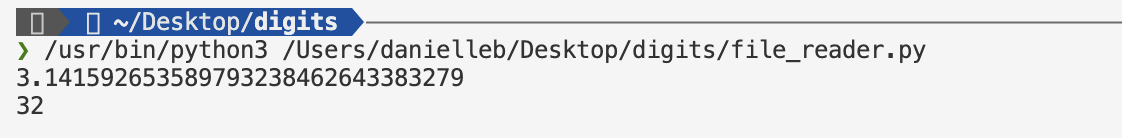

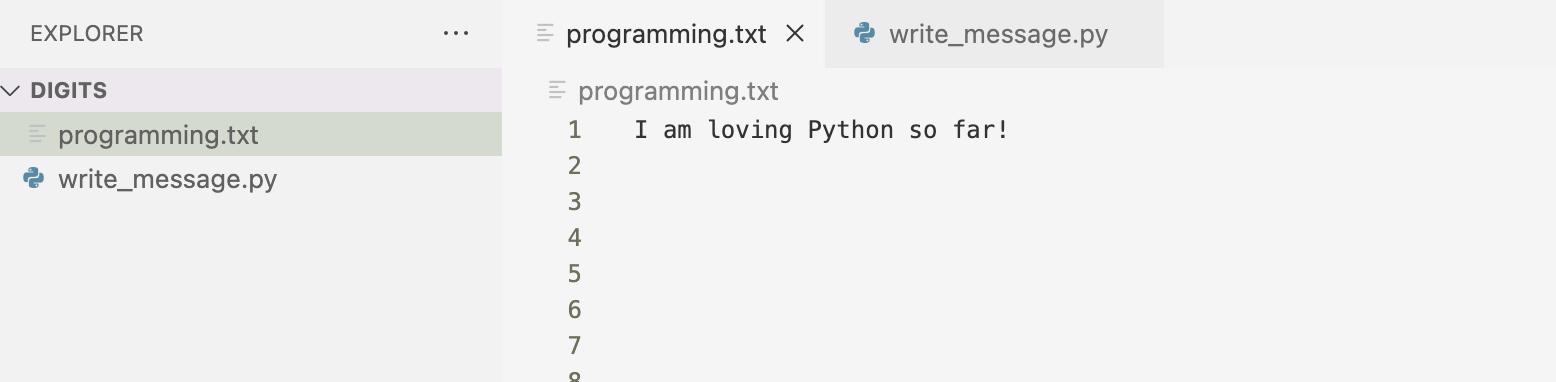

I can write to a file using the write_text() method. The example below shows a message that I want to write to the programming.txt file. When I run my code, there is no terminal output.

However, if I open the programming.txt file, I’ll see the message that I wrote.

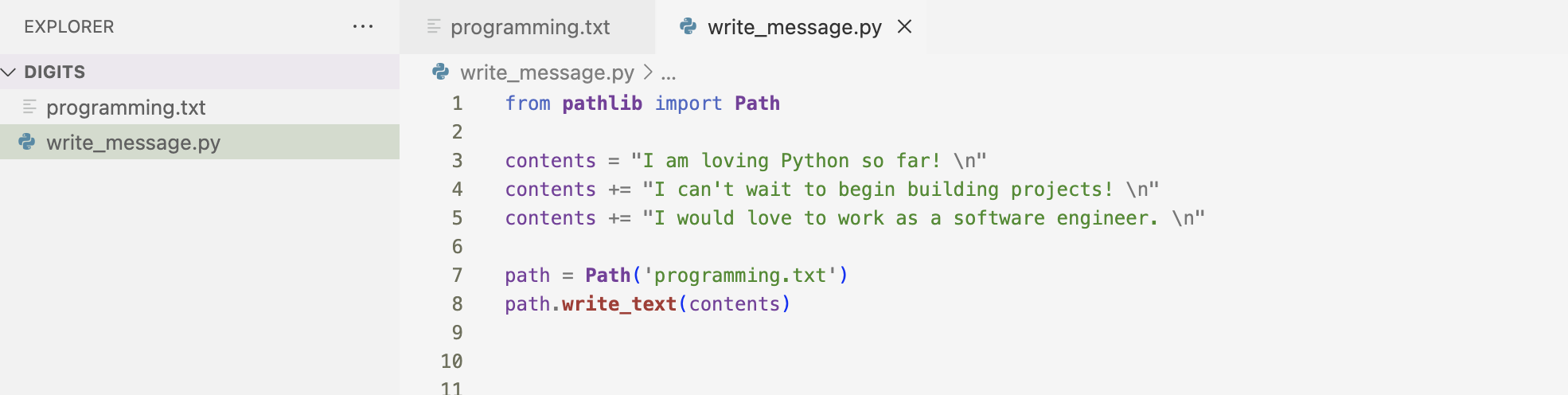

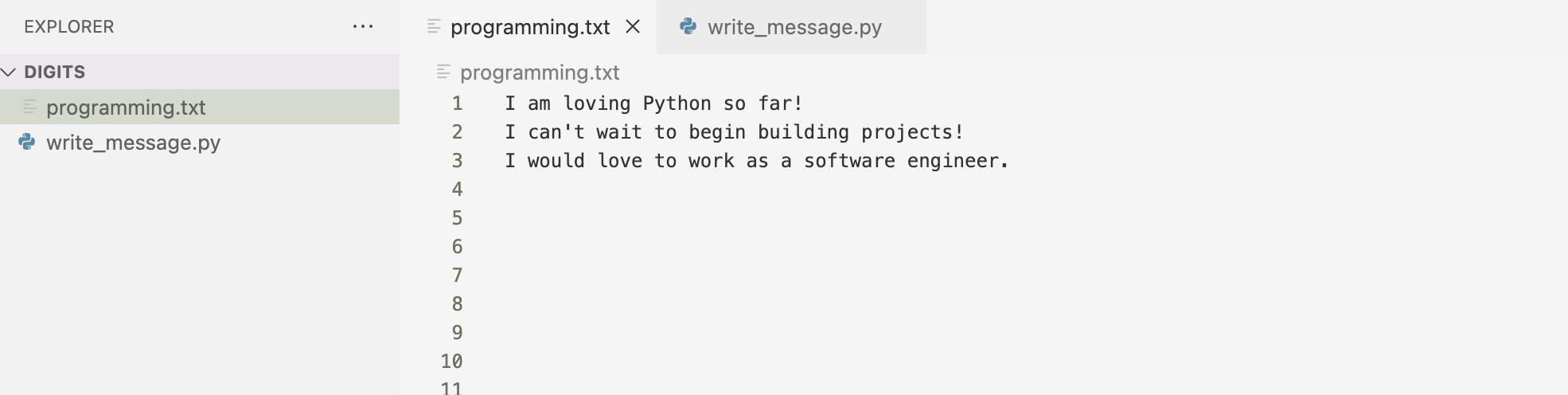

The example above demonstrates writing a single line to a file but I can write multiple lines to a file.

Exceptions

An exception is a special object that is used to manage errors that arise during a program’s execution. Whenever an error occurs in Python, it creates an exception object. If I write code to handle the exception, my program will continue to run but if I don’t the program will halt and show a traceback, a report of the exception that was raised.

Exceptions are handled with try-except blocks. A try-except block asks Python to do something, but will also tell Python what to do if an exception is raised. It will help my program continue to run even if things go wrong.

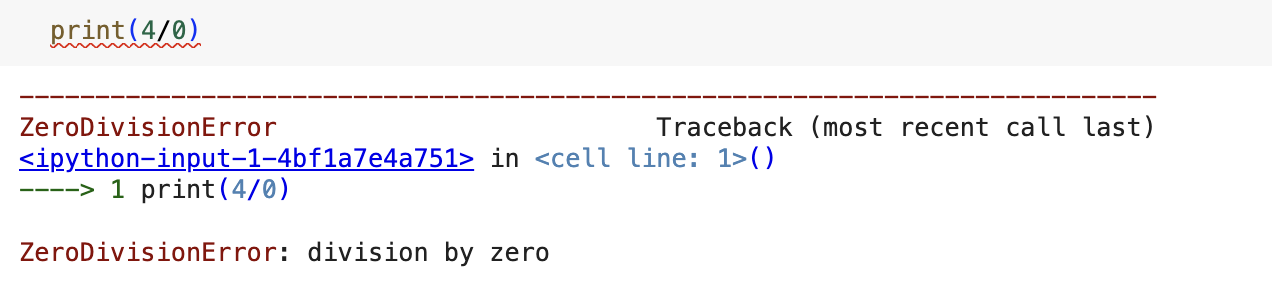

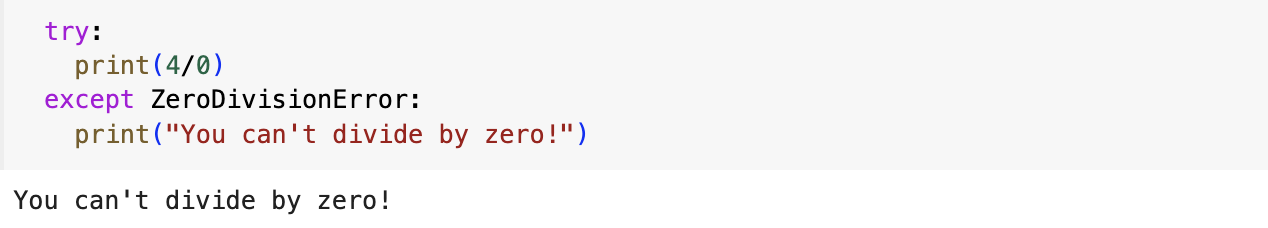

The first exception I learned about was the ZeroDivisionError exception. This is raised when I try to divide a number by zero.

Here is my attempt to divide by zero. I get a traceback telling me that the ZeroDivisionError was raised.

Here I write a try-except block to handle that exception. I put the print(4/0) statement (the line that caused the error) inside the try block. If the code works in the try block, Python skips over the except block. If the code in the try block raises an error, Python looks for an except block whose error matches the one that was raised, and runs the code in that block. In this case, Python looked for an except block that matched the ZeroDivisionError exception and ran the code print("You can't divide by zero!").

Exceptions are very useful as they can prevent crashes by prompting for more valid input. To make a program more error resistant, I could add an else block to my try-except block. Any code that depends on the try block executing successfully goes in the else block. The format would look something like this.

try:

answer = int(first_number) / int(second_number)

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("You can't divide by zero!")

else:

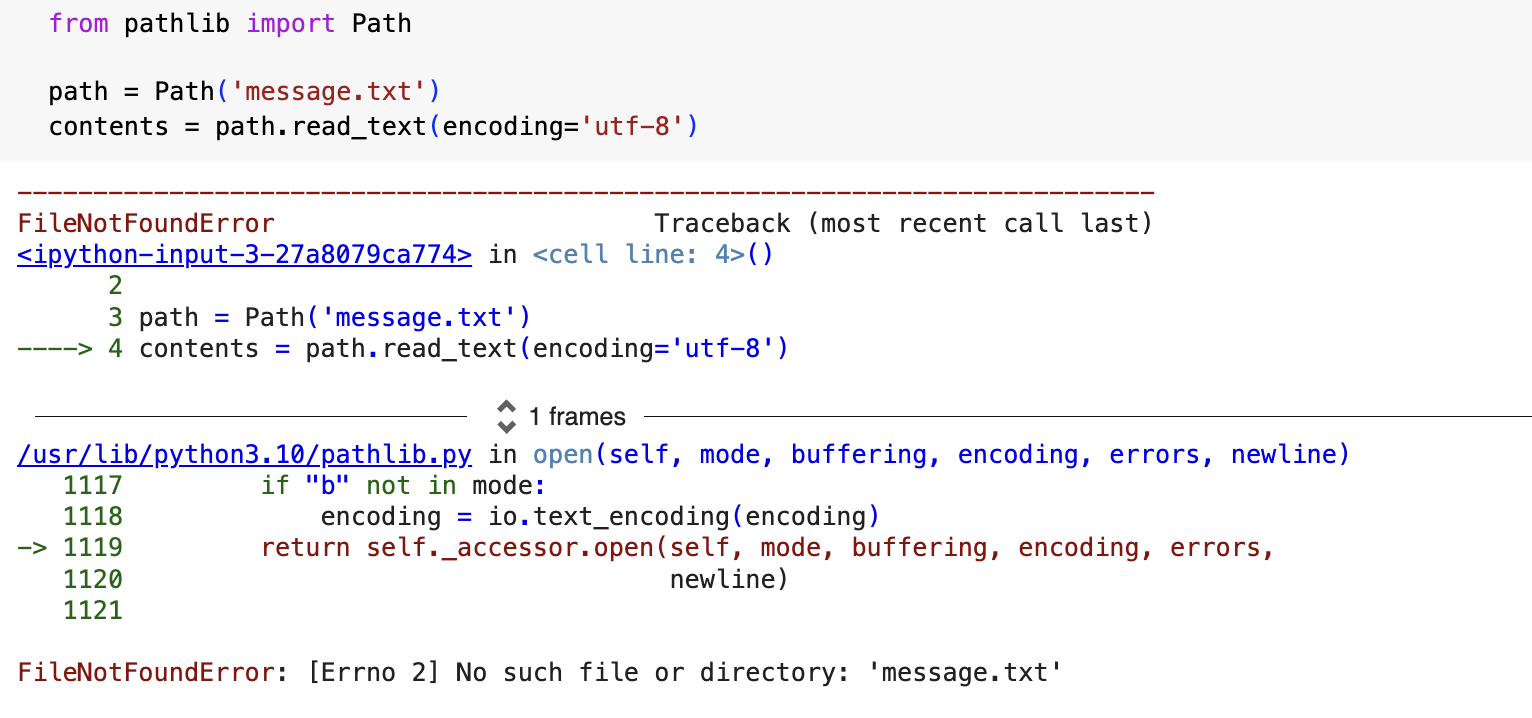

print(answer)The other kind of exception that was discussed in the book was the FileNotFoundError exception. This exception is raised when the file I’m looking for is in another location, the filename might be misspelled or the file might not exist at all. I can handle all of this using the try-except block.

Here is the I’m trying to read a message.txt file. I’m using the encoding argument inside the read_text() method. this argument is needed when my system’s default encoding doesn’t match the encoding of the file that’s being read. This usually occurs when the file I’m trying to read was not created on my system. When running this code, the FileNotFoundError exception is raised.

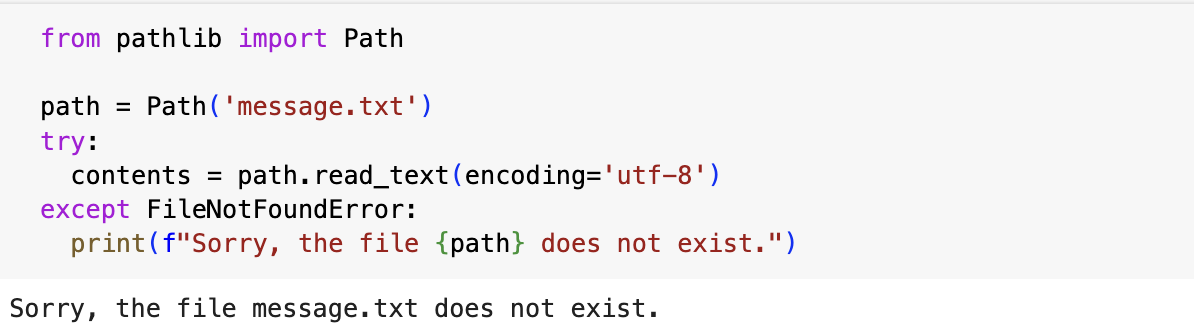

Here is put the code that raised the exception in the try block and I wrote an except block that matched the error. The result is a friendly message instead of a traceback.

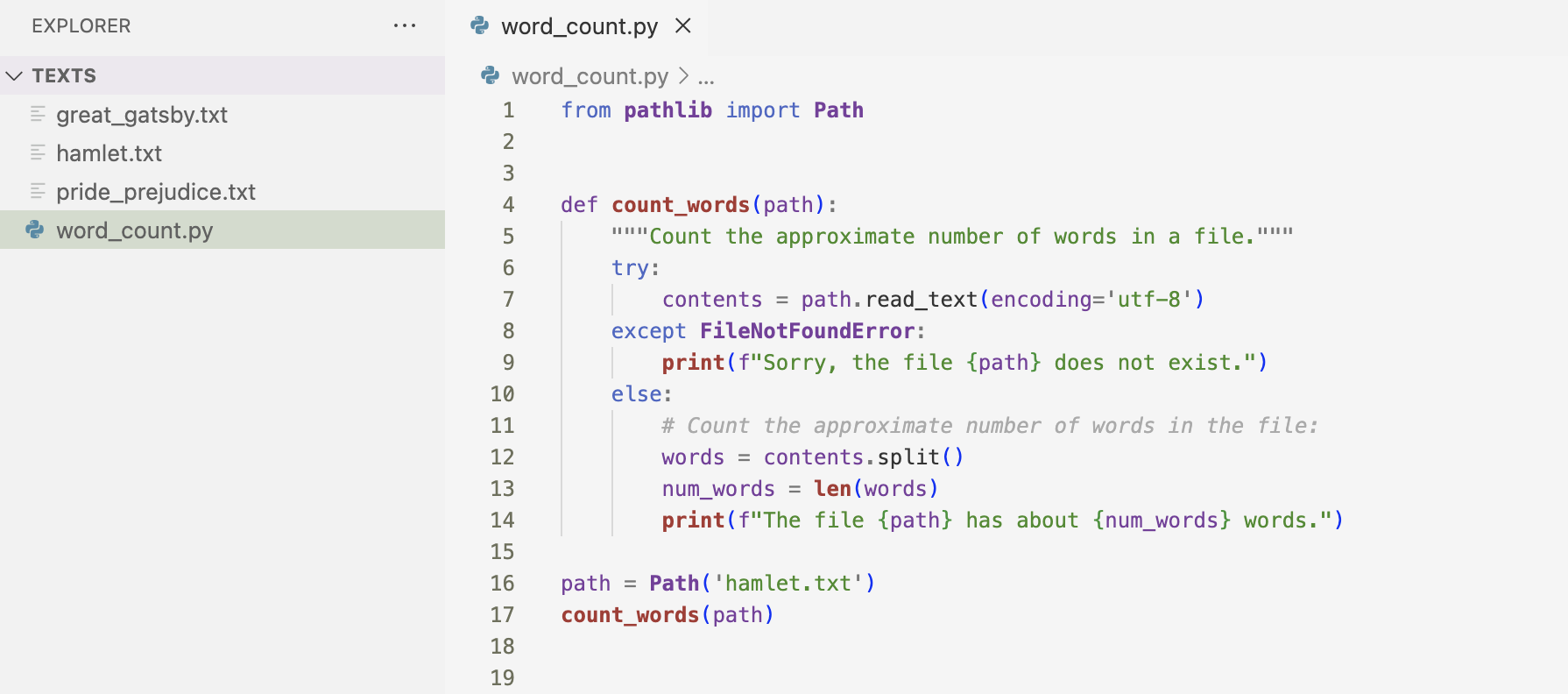

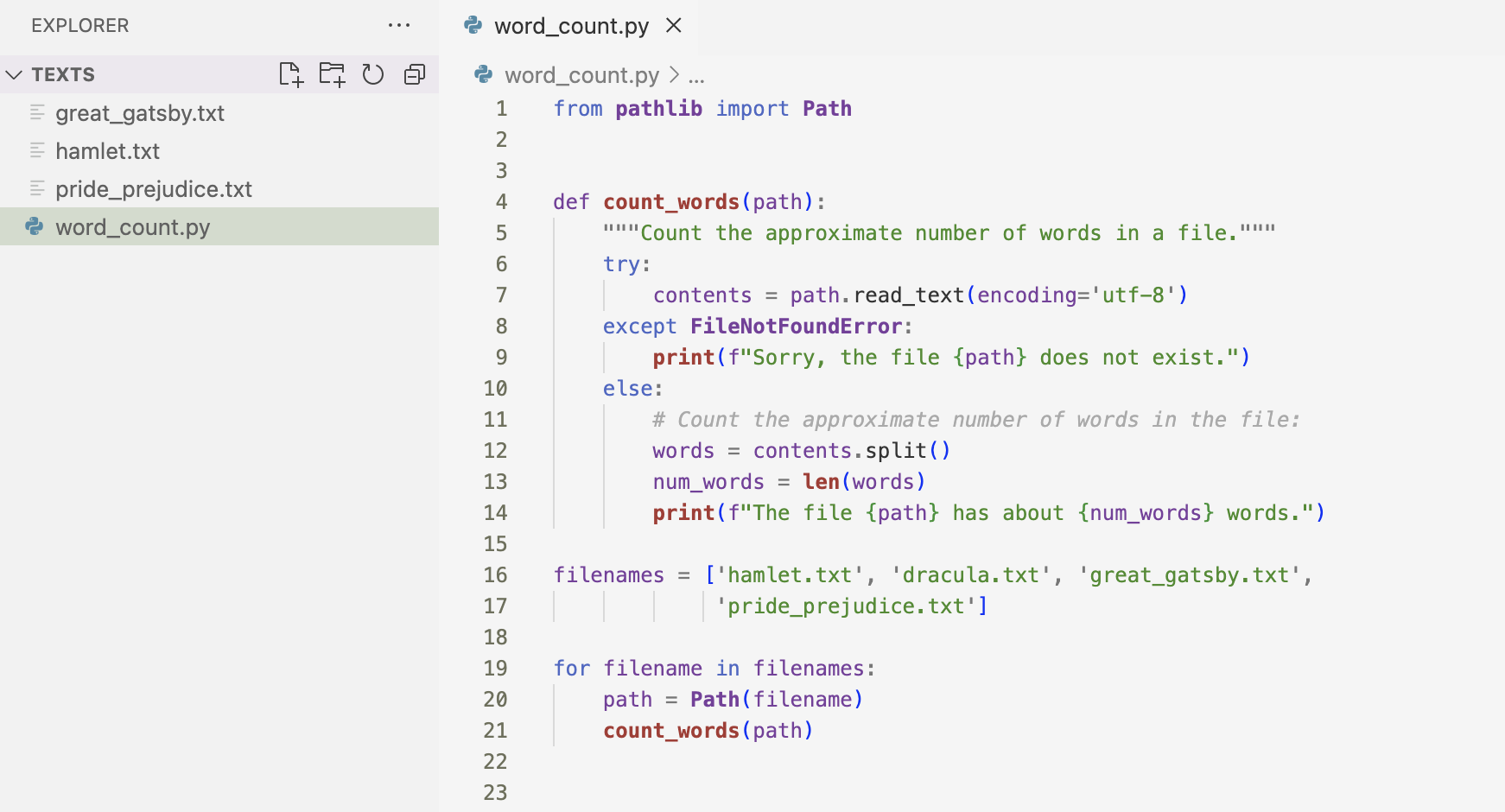

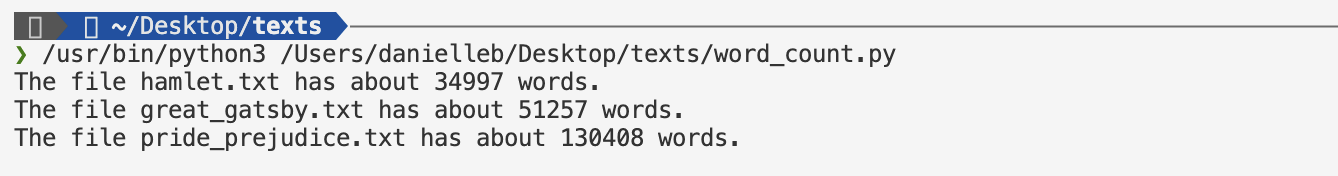

The next section of the chapter goes into analyzing text. I used the example in the book using the Hamlet text file to count the number of words in the text. I used the string method split(), which splits a string wherever it finds any whitespace.

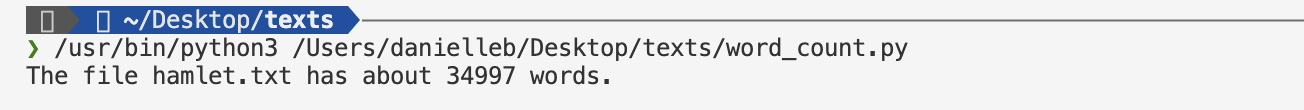

Here is the result of the code above.

Here is an example where I work with multiple files.

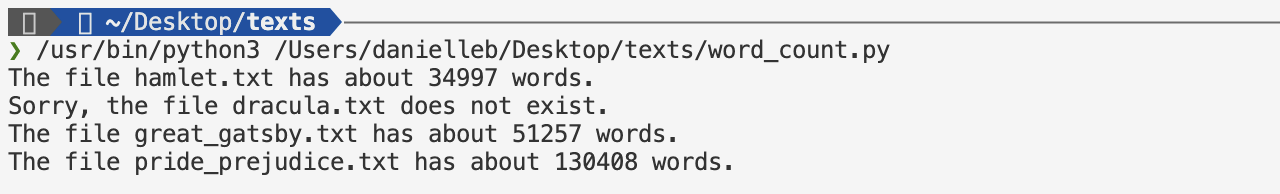

The result of looping through the multiple text files is below.

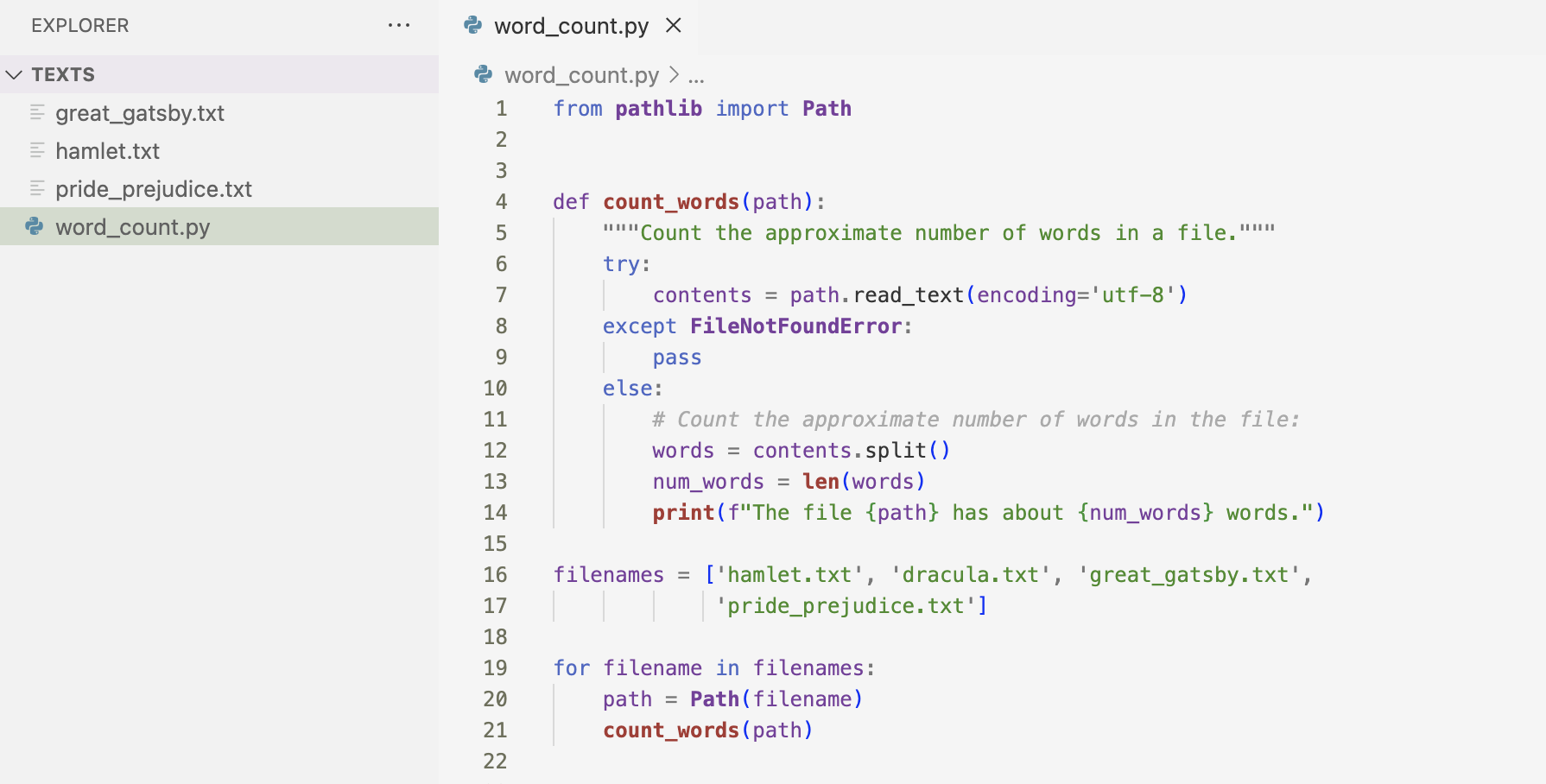

The previous example I informed users that one of the files was unavailable. There are certain situations where I would want the program to fail silently. I used pass to make a program fail silently. The pass statement tells Python to do nothing in the except block.

Because I used the pass statement, when it reaches the file that does not exists, the program simply continues to run as if nothing happened. It prints out the word count of the files that do exist.

Storing Data

Programs will often asks users to input certain kinds of information. When I create my program, I want to be able to save the information they entered when they close my program. I can use the json module to store my data. The json module allows me to convert Python data structures into JSON-formatted strings and load the data from that file the next time the program runs. The JSON format is not specific to Python so I can share data that I stored in the JSON format with folks who work in other programming languages.

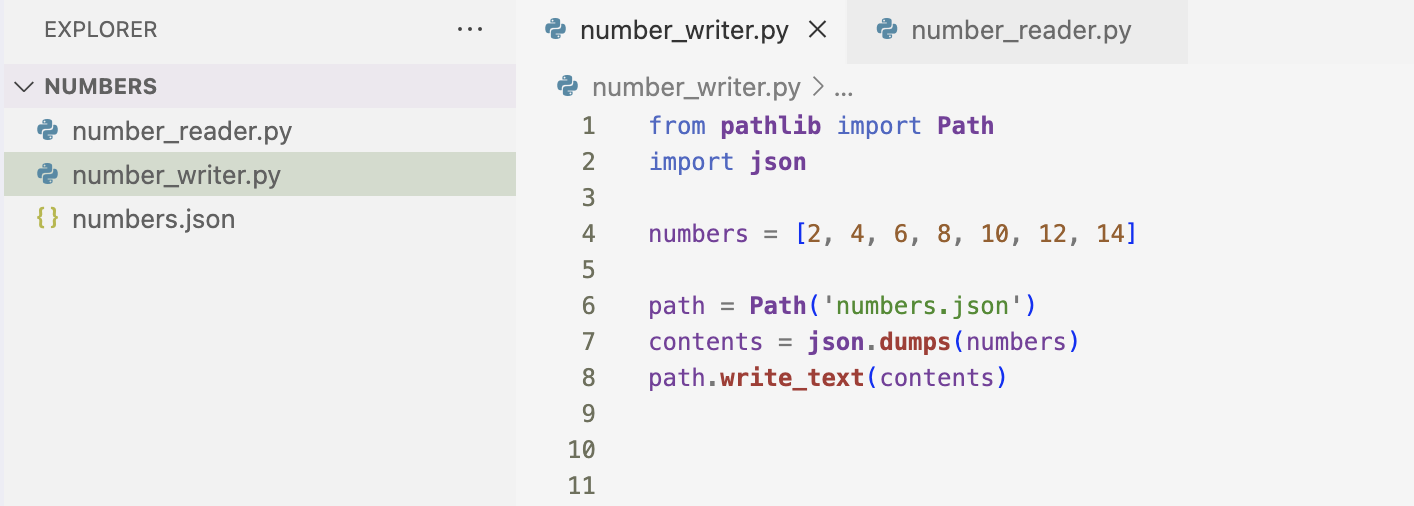

Here I wrote a program that stores a set of numbers and another program that reads these numbers back into memory. I’ll use the method json.dumps() to store the set of numbers. The json.dumps() method takes only one argument: the piece of data that should be converted into the JSON format.

I first imported the json module, and then created a list of numbers to work with. Next, I chose a filename in which to store the list of numbers. I use json.dumps() mtehod to generate a string the JSON representation of the data I’m working with. Once I have the string, I write to it to the file using write_text(). This program has no output, but it creates a numbers.json file that stores my data.

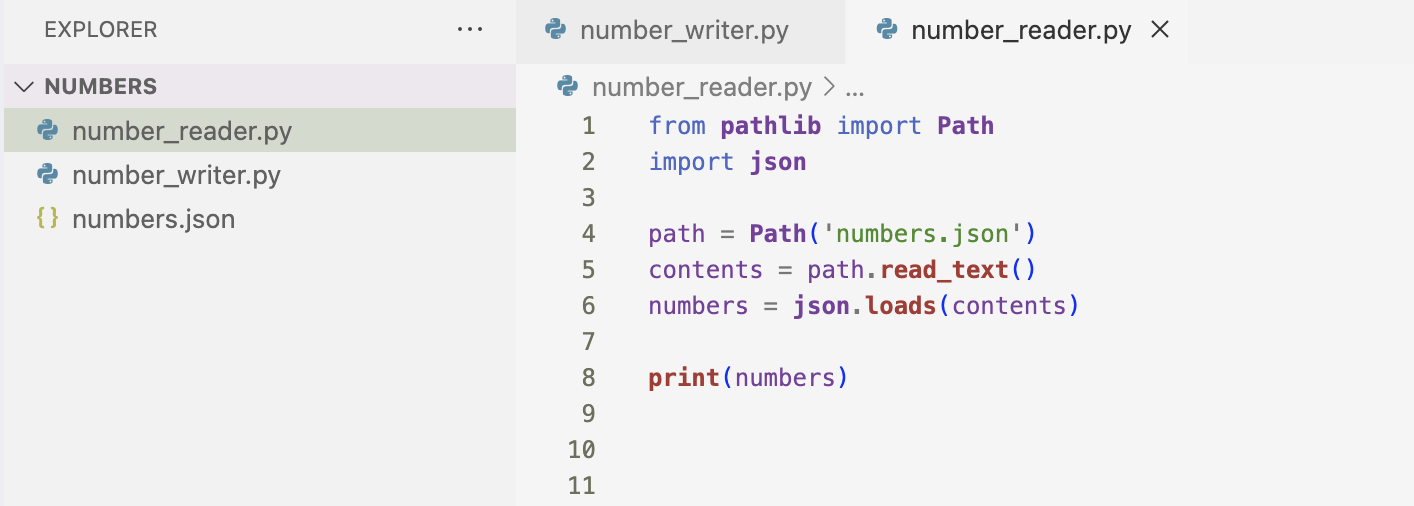

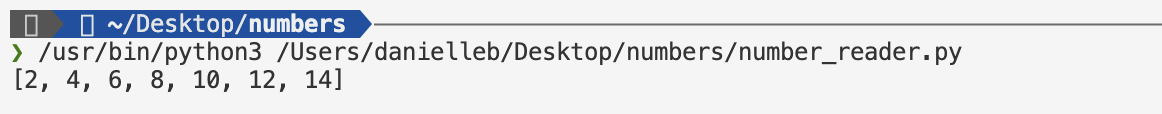

Here I am using json_loads() function to read the list back into memory. I made sure to read from the same file I wrote to. Then, I read the file with the read_text() method. I pass the contents of the file to json.loads(). This takes in a JSON-formatted string and returns a Python object which I assigned to numbers.

Here is the result of printing the recovered list of numbers. It is the same list I created before.

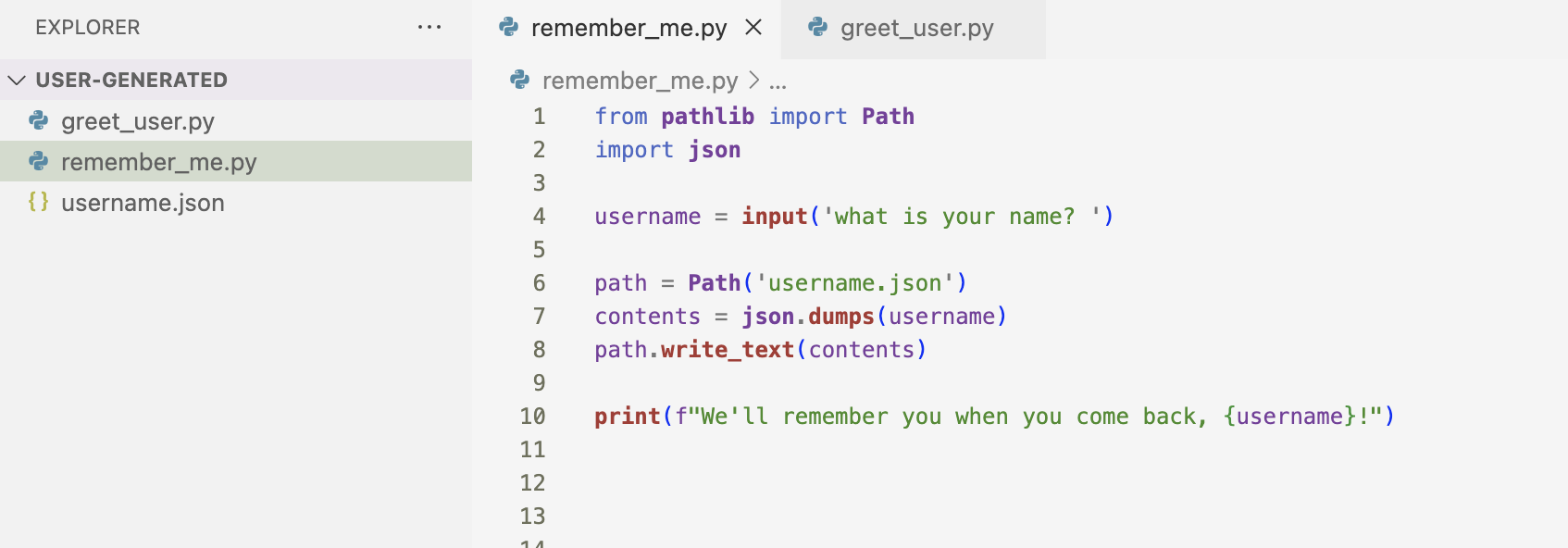

I am going to use the same concepts to save and read user-generated data.

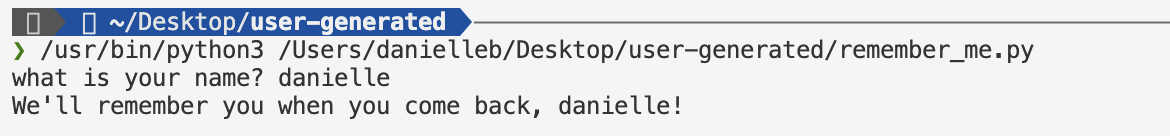

I prompted to user for their name, saving the input to a variable called username. I write data I collected to a file called username.json. I printed a message telling the user that I’ll remember them when they come back.

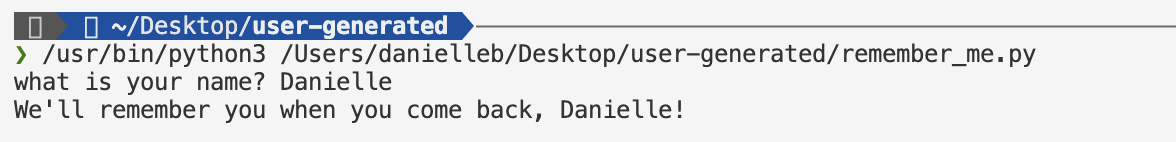

When I run the above code block, it prompts me for my name, prints the message and creates the username.json file.

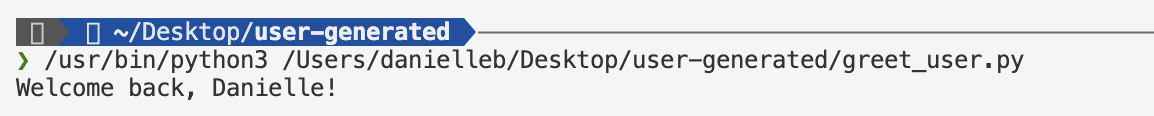

The code block below greets the user whose name has already been stored. I read the contents of my file and use json.loads() to assign the recovered data to the variable username. When the username is recovered, I welcome the user back with a message.

Here is the output of the code block.

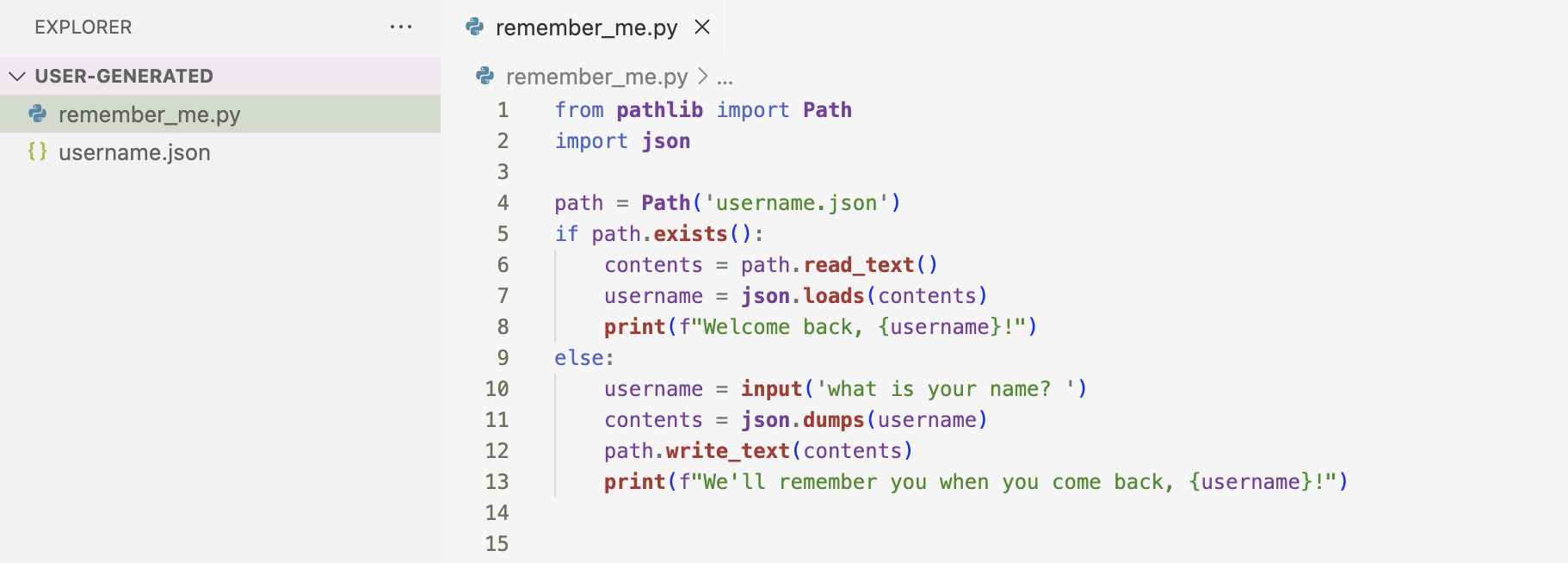

I can combine the two programs into one using and if-else statement and the exists() method. This method returns True if a file or folder exists and False if it doesn’t. If the username.json file exists, I load the username and print a greeting to the user. If the username.json file doesn’t exist, I prompt the user for their name, store the value the user entered and tell the user that I’ll remember them when they come back.

Refactoring

There will come a time where I’ll recognize that I can improve my code by breaking it up into a series of functions that have specific jobs. The process of restructuring existing code without changing its behavior is called refactoring.

Here I have a function that calculates the total price of an item. It calculates the subtotal and if that item is discounted, I subtract the discount from the subtotal ; otherwise, it return the subtotal.

def calculate_total_price(quantity, price_per_unit, discount):

subtotal = quantity * price_per_unit

if discount:

subtotal -= discount

return subtotalWhile this code work, it can be broken up into parts. This makes my code cleaner, easier to understand, and easier to extend.

The code above can be broken up into three different functions: a function to calculate the subtotal of the item, a function to apply the discount to the item and a function to calculate the total price of the item.

def calculate_subtotal(quantity, price_per_unit):

return quantity * price_per_unit

def apply_discount(subtotal, discount):

if discount:

return subtotal - discount

return subtotal

def calculate_total_price(quantity, price_per_unit, discount):

subtotal = calculate_subtotal(quantity, price_per_unit)

return apply_discount(subtotal, discount)I’m almost at the finish line. Moving on to the last chapter of part one, Chapter 11!