Chapter 9 discussed object-oriented programming(OOP) and classes.

Object-oriented programming is a way of structuring a software program around objects.

In object-oriented programming, classes represent real-world things and situations and objects are based on these classes. Classes combine functions and data into one package that can be used in flexible and efficient ways. Creating an object from a class is called instantiation, and I’ll work with instances of a class. An instance is a single object created from a class.

I’ll start by creating and using a class.

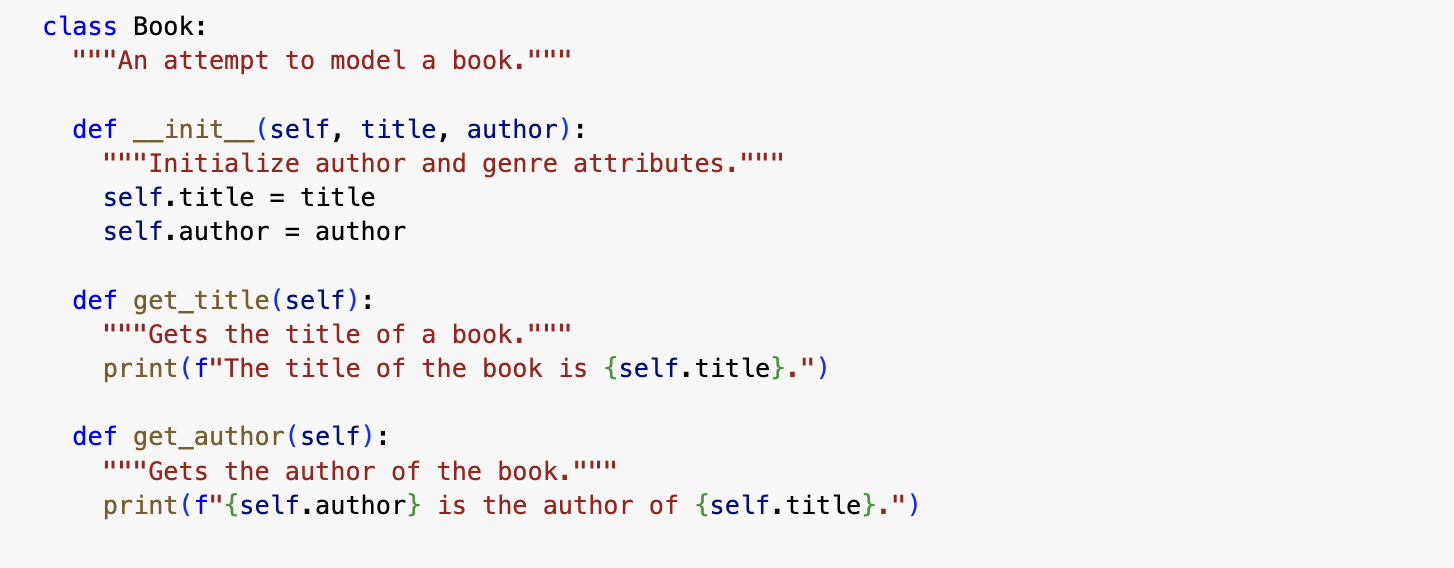

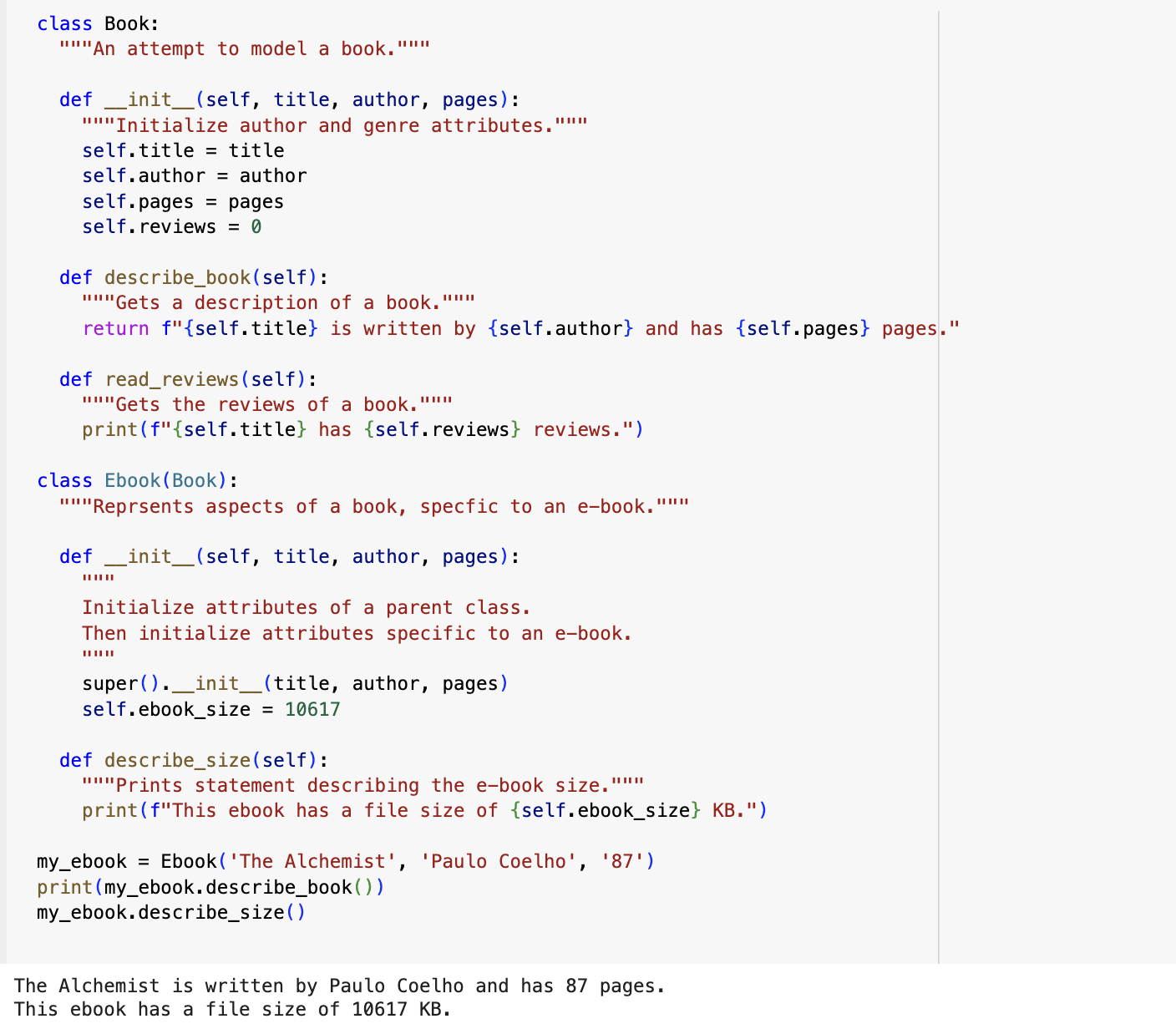

I first defined a class called Book. Capitalized names refers to classes in Python.

A function that’s part of a class in called a method. The __init__() method is a special method that Python automatically runs whenever I create a new instance based on the Book class. I defined the __init__()method to take three parameters: self, title and author. I like to think of self as a special built-in button in Python methods. You always need to include it as the first argument when defining a method in a class. This is because whenever you call a method on an object (which is an instance of the class), Python automatically presses this button behind the scenes. The self parameter does two things: it gives the method a reference to the specific object it’s working on and this reference is stored in self. It allows the method to access the object’s unique attributes and other methods defined in the class.

When I pass Book, there is no need to pass self because it is passed automatically, however, I will pass title and author as arguments. When I want to make an instance from the Book class, I’ll only provide values for the title and author.

In the init() method, both variables are prefixed with self. When a variable is prefixed with self, it becomes accessible to all methods within the class, and any instance of the class can access these variables. For instance, self.title = title assigns the value of the parameter title to the variable title within the instance being created. Similarly, self.author= author assigns the value of the parameter author to the variable author within the instance. These variables, accessible through instances, are referred to as attributes.

The Book class has two other methods: get_title() and get_author(). We defined these methods to have one parameter, self. The instances I create will have access to these methods, so I’ll be able to get the title and author of a book. Right now, they do not do much.

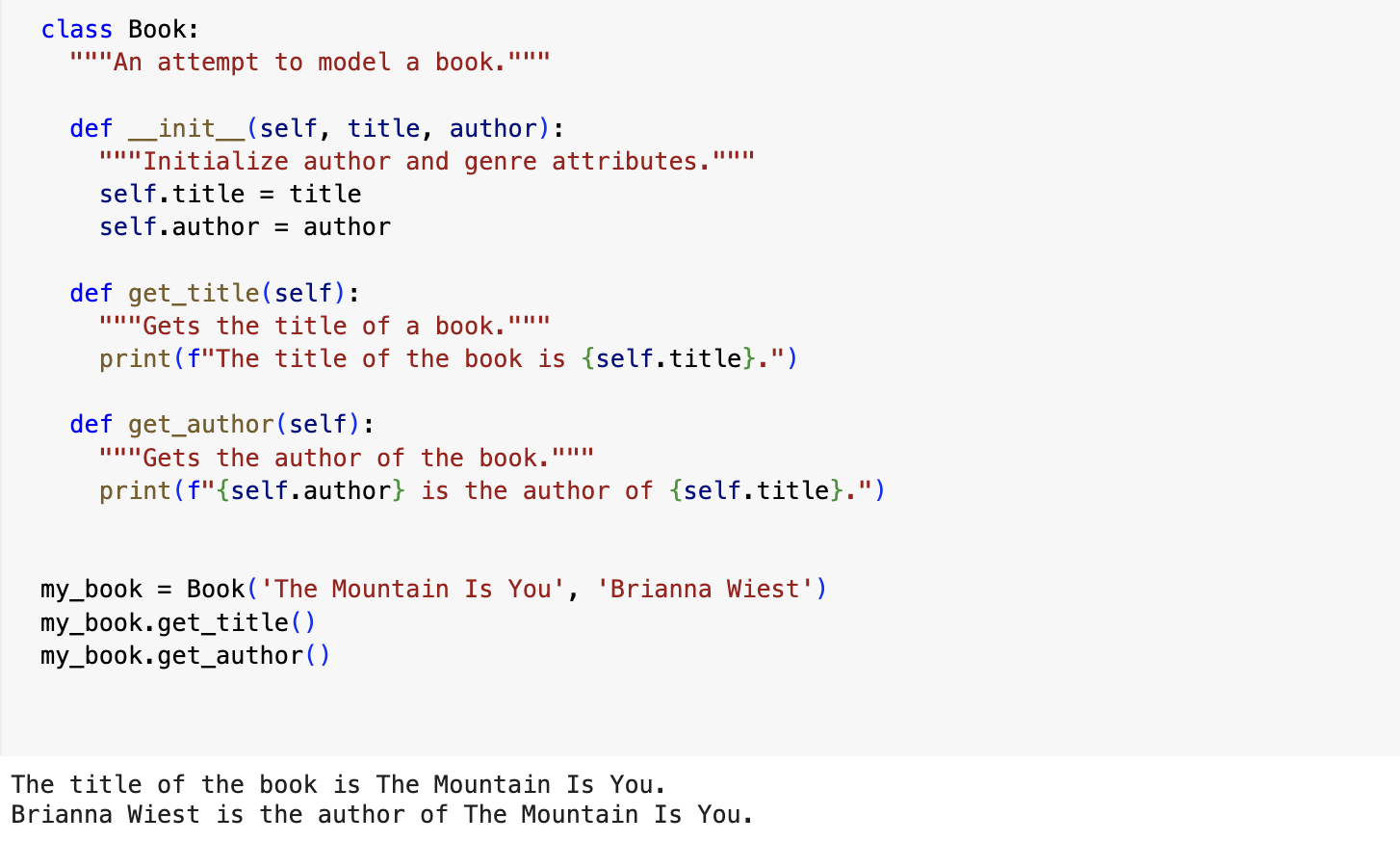

I extended the previous example by making an instance from my Book class. I tell Python to create a book whose title is called ‘The Mountain Is You’ and whose author is ‘Brianna Wiest’.

When Python reads this line, it calls the init() method in Book with the arguments ‘The Mountain Is You’ and ‘Brianna Wiest’. The init() method creates an instance representing this particular book and sets the title and author attributes using the values we provided. Python then returns an instance representing this book. We assign that instance to the variable my_book.

I can access the attributes of an instance using dot notation. I can access the value of my_book ’s attributes by writing my_book.name with name representing the attribute. I use dot notation below to call get_title() and get_author().

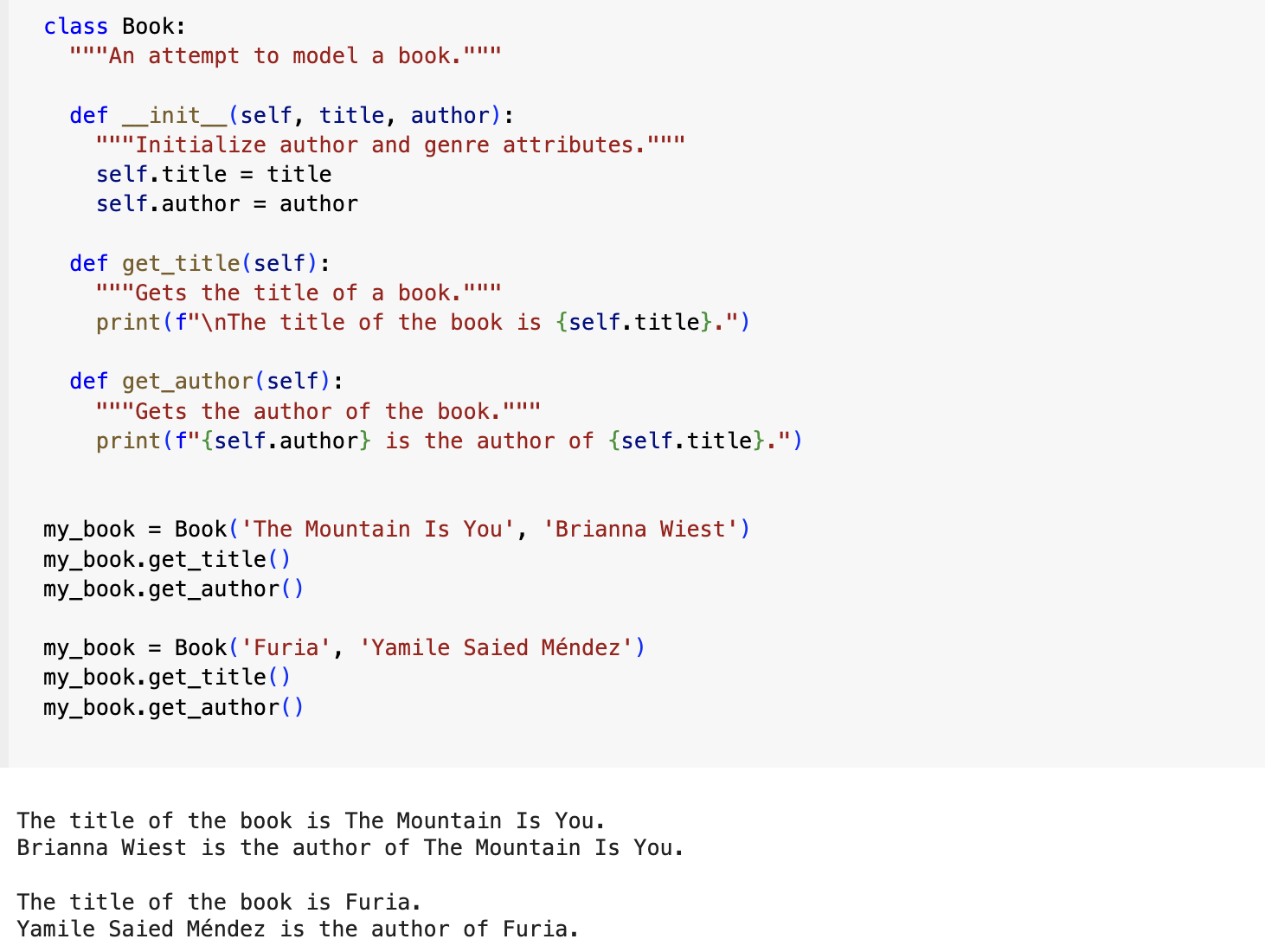

I can create multiple instances from a class. I expanded the example even further by adding a second instance. Each book is a separate instance with its own set of attributes, capable of the same set of actions.

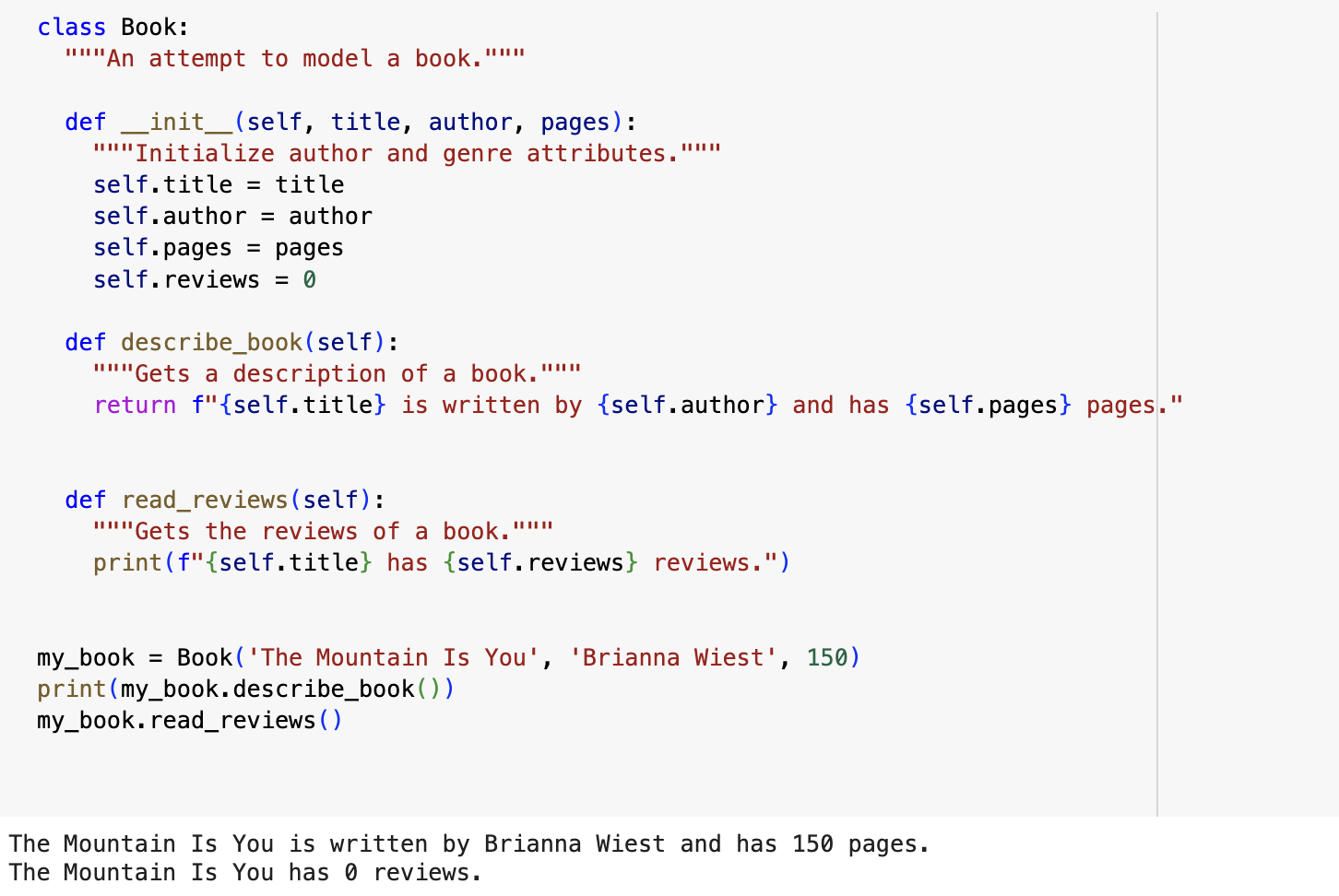

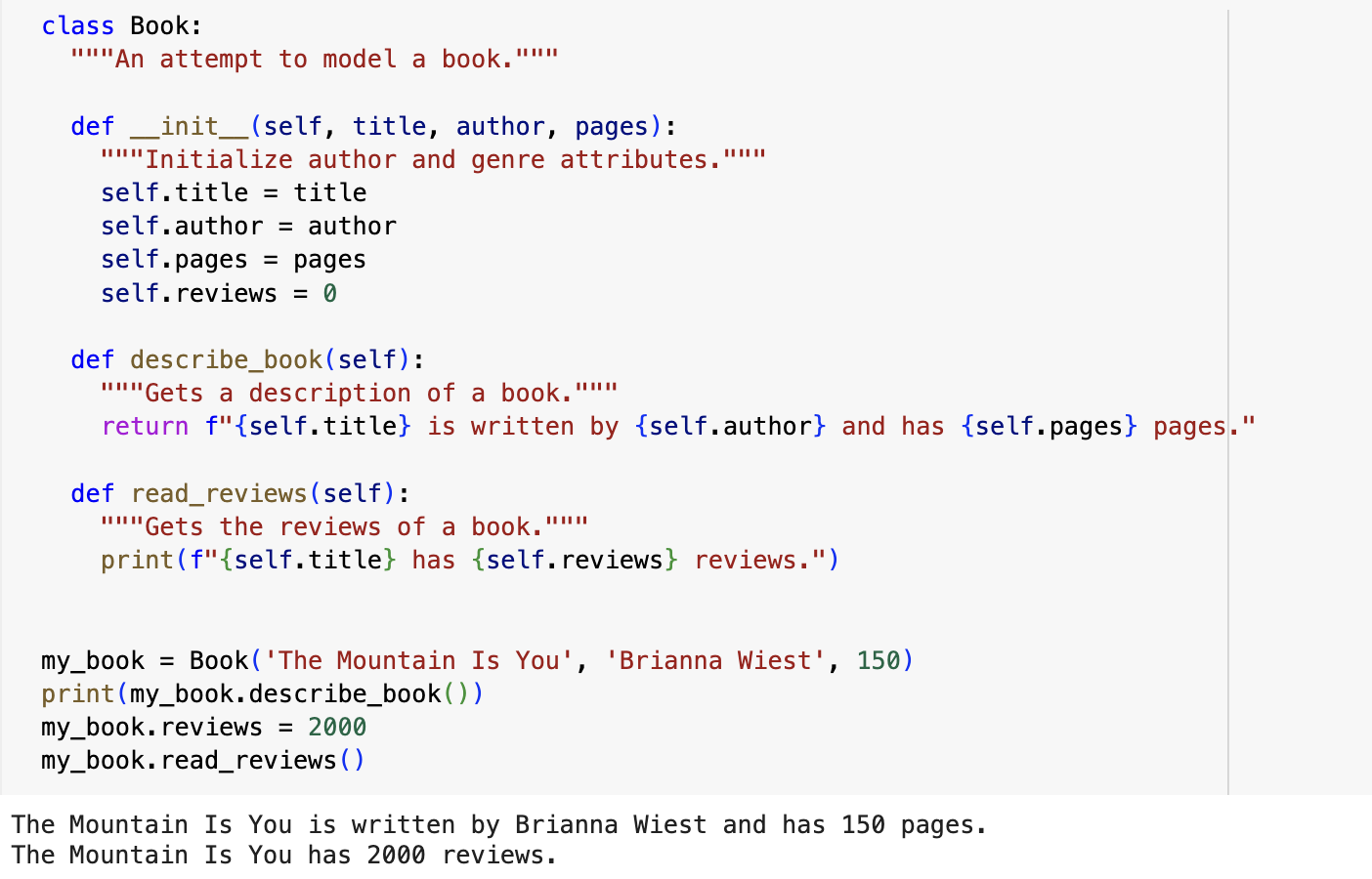

When an instance is created, attributes can be defined without being passed in as parameters. These attributes can be defined in the __init__() method, where they are assigned a default value.

Continuing with the Book example, I extended the example by adding a pages attribute. When Python calls the __init__() method to create a new instance, it stores the title, author and pages attributes like it did previously. Python, then creates a new attribute called reviews and sets its initial value to 0. There is a new method called read_reviews that gets the number of reviews a book has.

I can modify attributes in three ways. Let’s look at the first way.

The first (and simplest) way to modify the value of an attribute is to access the attribute directly through an instance. I used dot notation to access the book’s reviews attribute, and set its value directly. Python takes my_book, finds the attribute reviews associated with it, and set the value of that attribute to 2000.

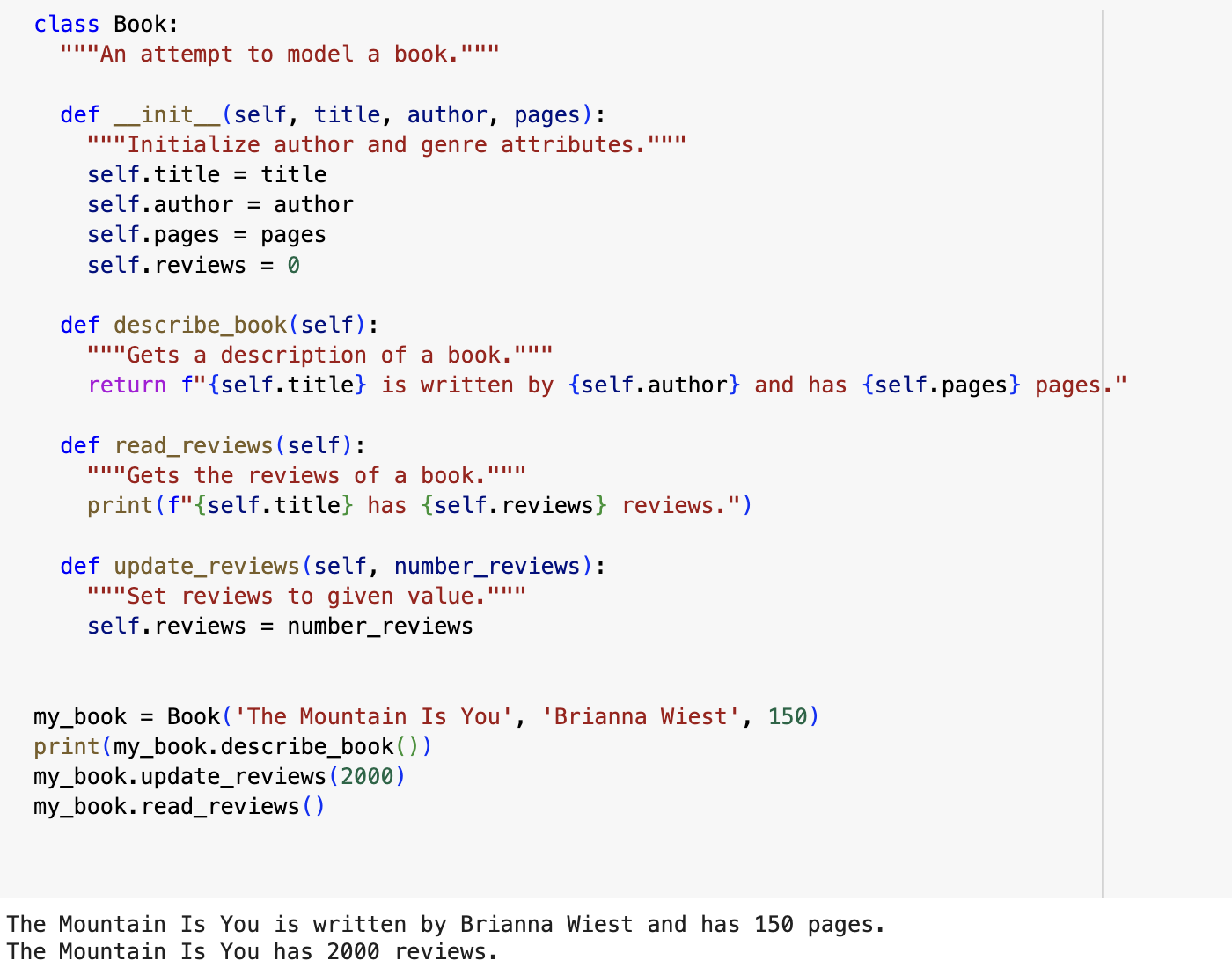

Another way is to modify an attribute’s value through a method. Instead of accessing the attribute directly, I create a new method called update_reviews and pass the new value to that method.

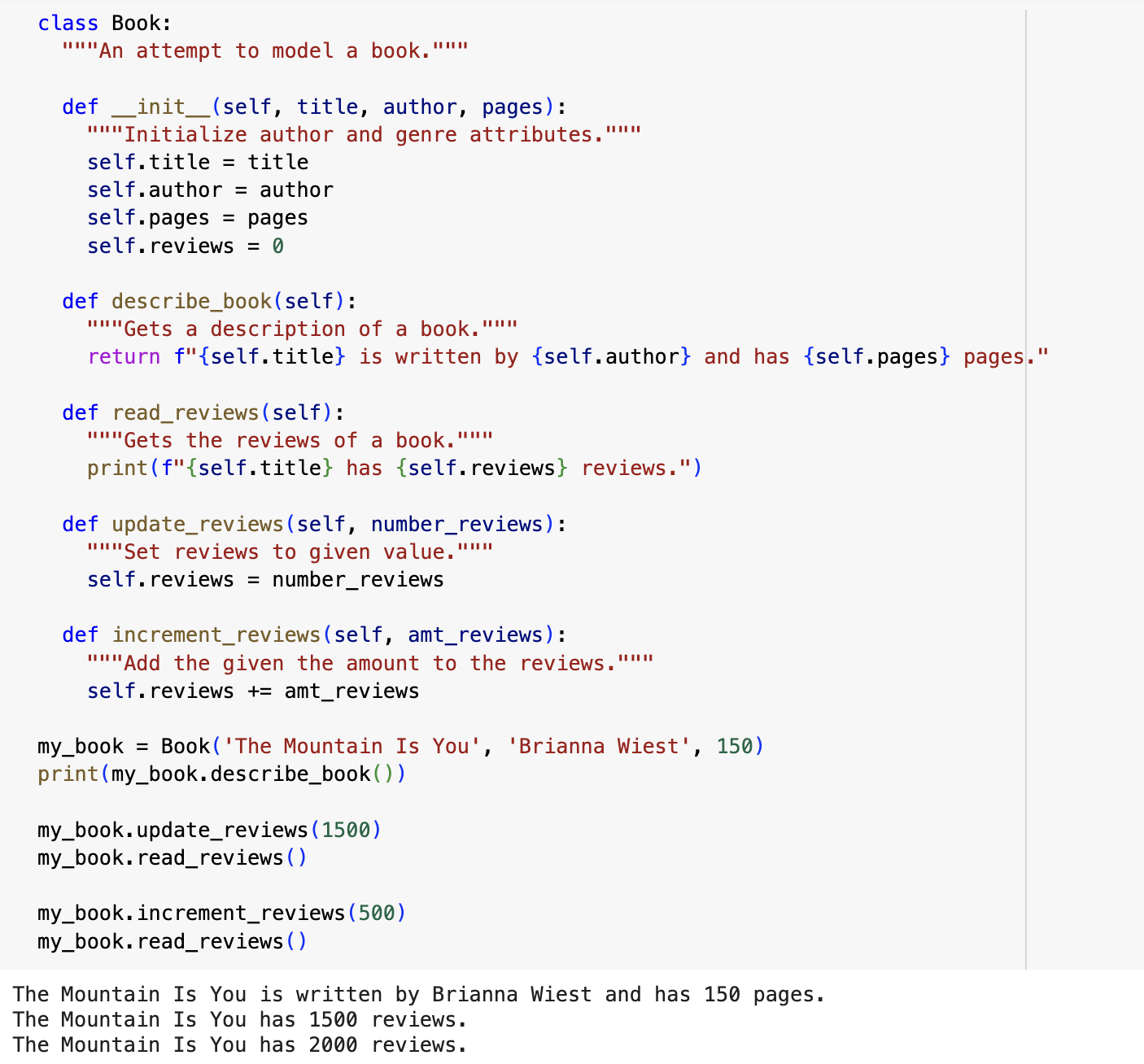

Instead of setting an entirely new value, I can increment an attribute’s value by a certain amount. Say that the book initially had 1500 reviews and I want to add 500 to this value. The method increment_reviews allows me to pass the the increment amount and add that value to reviews.

Inheritance

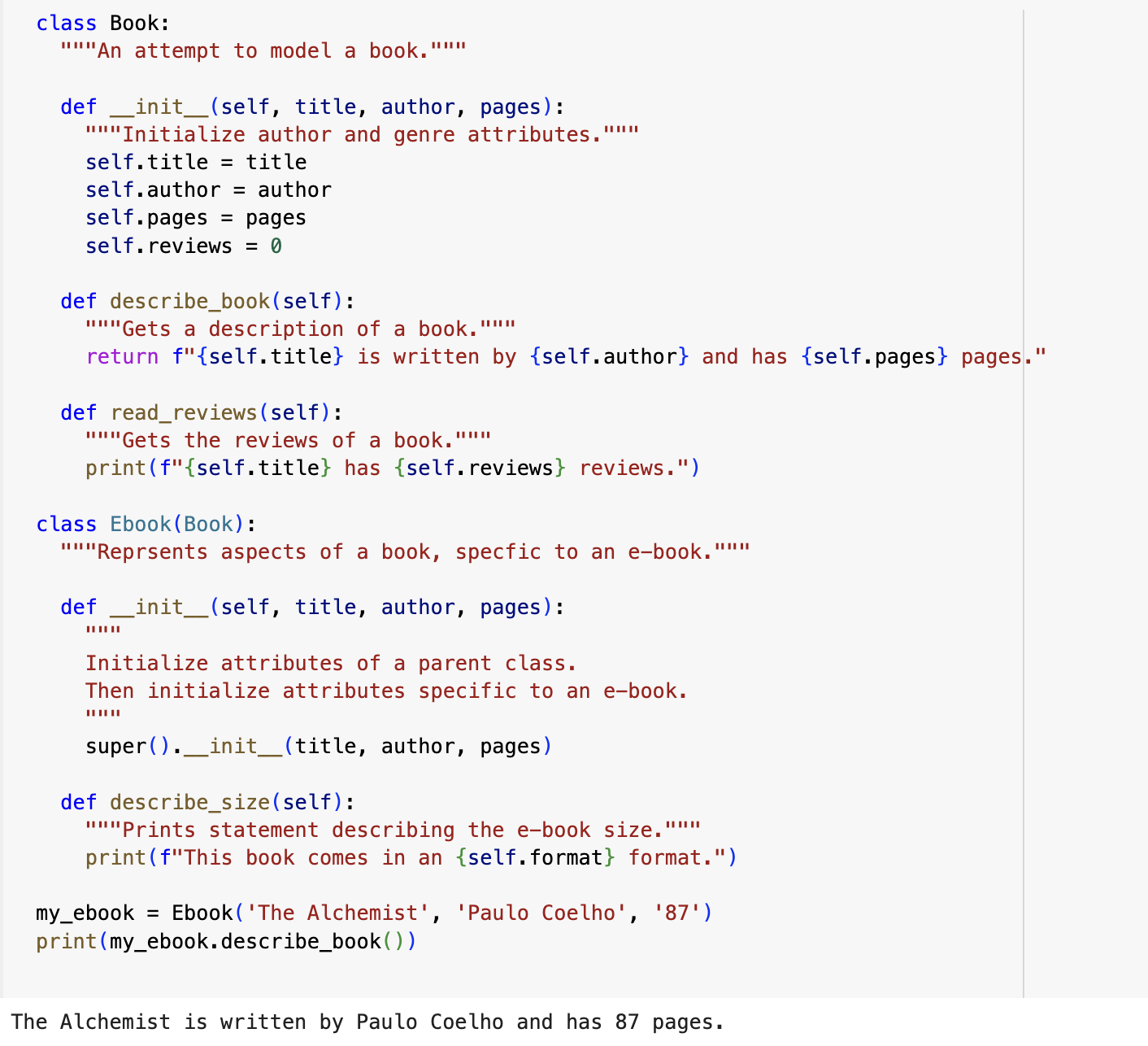

Inheritance is a fundamental concept in object-oriented programming (OOP) that allows me to create a new class that inherit properties and behaviors from existing class. The original class is called the parent class and the new class is called the child class. A child class builds on its parent class. It gets all the parent’s methods and attributes but can also define its new methods and attributes of its own.

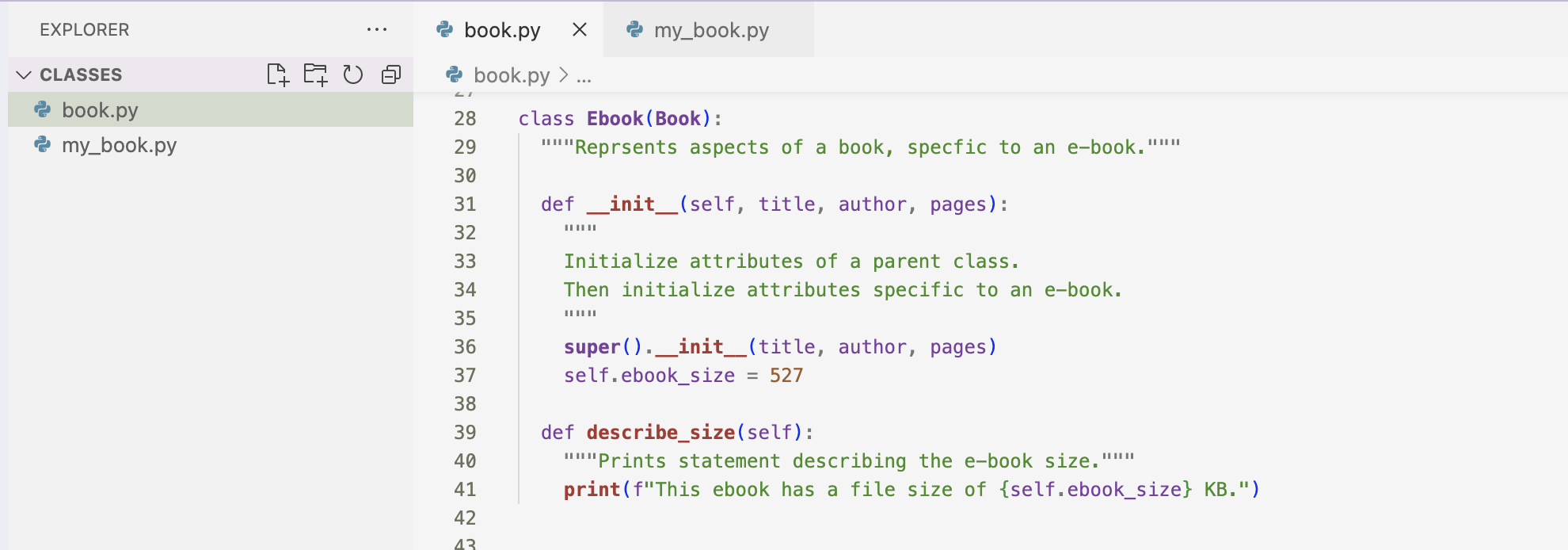

I started with Book. When I create a child class, the parent class must be part of the current file and must appear before the child class in the file. I then defined the child class, Ebook. The name of the parent class must be included in parentheses in the definition of a child class. The init() method takes in the information required to make a Ebook instance.

The super() function is a special function that allows me to call a method from the parent class. This line tells Python to call the init() method from Book, which gives an Ebook instance all the attributes defined in that method. The name super comes from a convention of calling the parent class a superclass and the child class a subclass.

I tested whether inheritance is working properly by trying to create an ebook with the same kind of information we’d provide when making a regular book. I made an instance of the Ebook class and assigned it to my_ebook. This line called the init() method defined in Ebook, which in turn told Python to call the init() method defined in the parent class Book. I provided the arguments ‘The Alchemist, ’Paulo Coelho’, and 87.

I can add new attributes and methods for my child class, Ebook. I added a new attribute called genre and a method describe_encyclopedia() to report on this attribute. I created the self.genre attribute and set it to ‘reference’. This attribute will be associated with all the instances created from the Encyclopedia class but will not be associated with any instances of Book. I added the describe_encyclopedia() method that prints information about the encyclopedia.

With inheritance, I can override any method from the parent class that doesn’t fit what I’m trying to model with the child class. I would define a method in the child class with the same name as the method I want to override in the parent class.

Sometimes, I may find myself adding more and more detail to a class. I may find that my growing list of attributes and methods causes my files to become lengthy. In cases like this, I can break my large class into smaller classes that work together in an approach called composition.

Importing Classes

Just as I did with functions, Python allows me to store classes in modules and then import the classes I need into my main program.

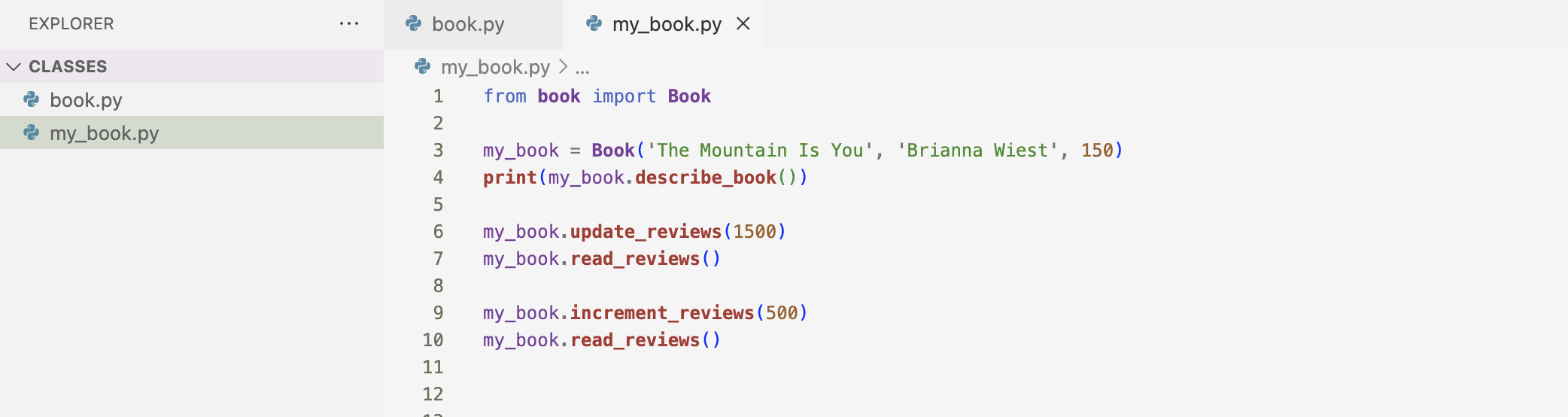

I’m going to use the previous book example where I incremented the number of reviews.

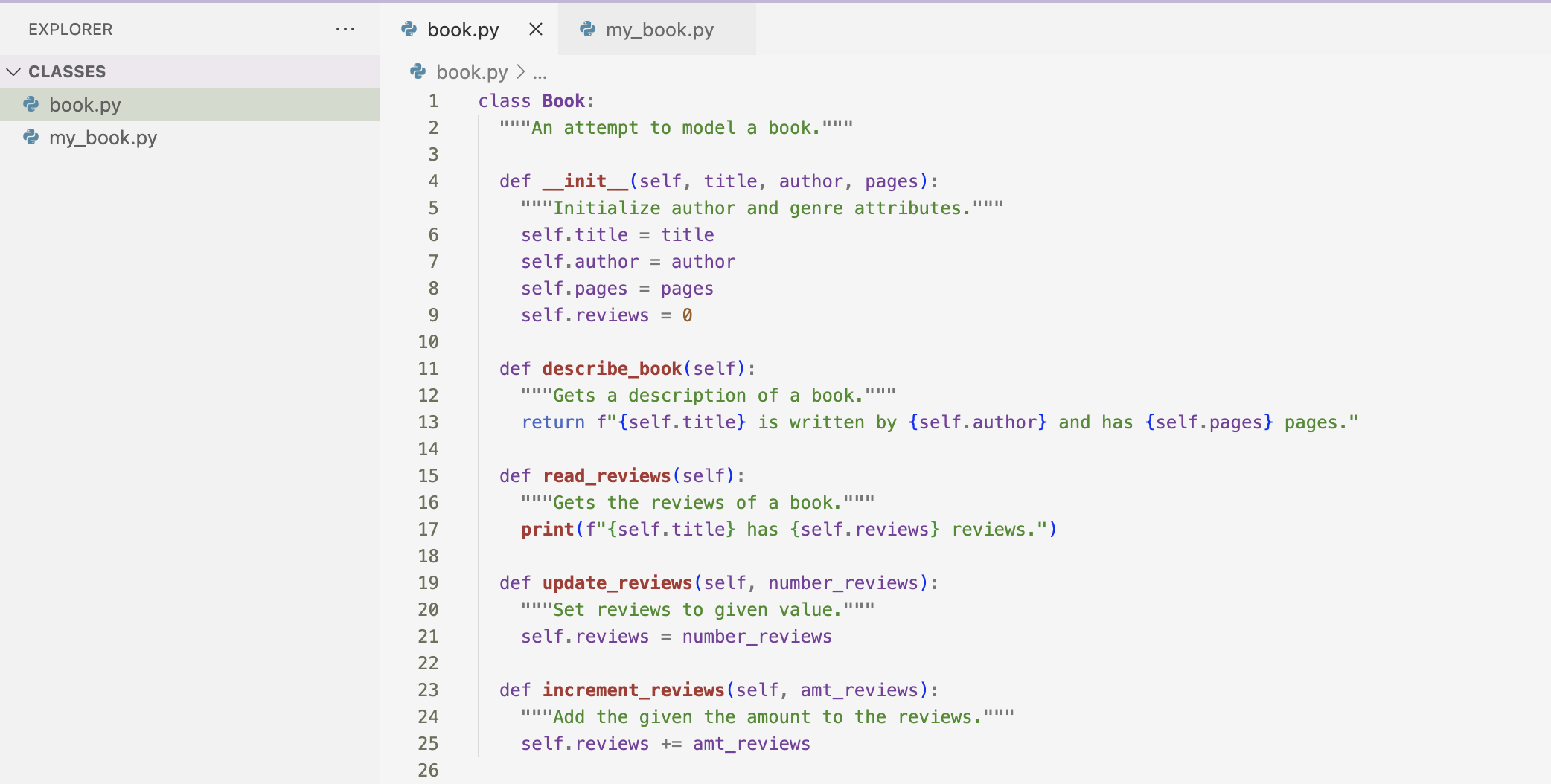

Below I have my class Book saved to a book.py file.

I created my_book.py file that will import the Book class and then create an instance from that class.

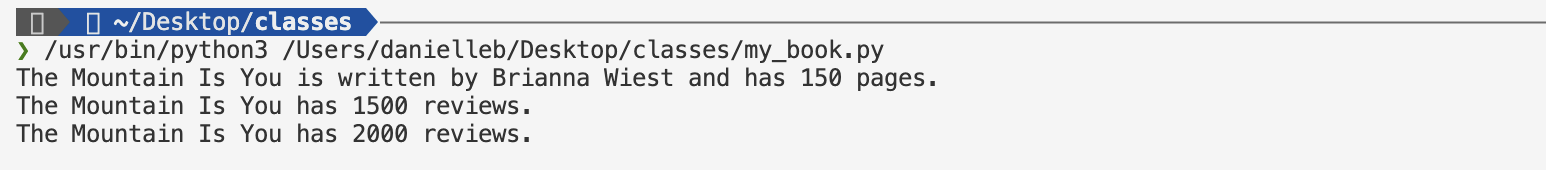

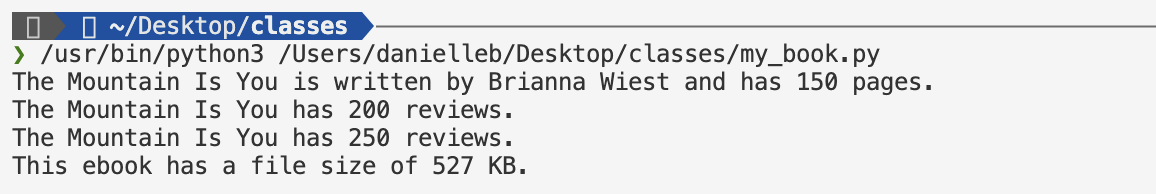

When I run the code, I get the same result as before.

I can store multiple classes in a module. In addition to the Book class, I stored my Ebook class and a new class I created called Audiobook.

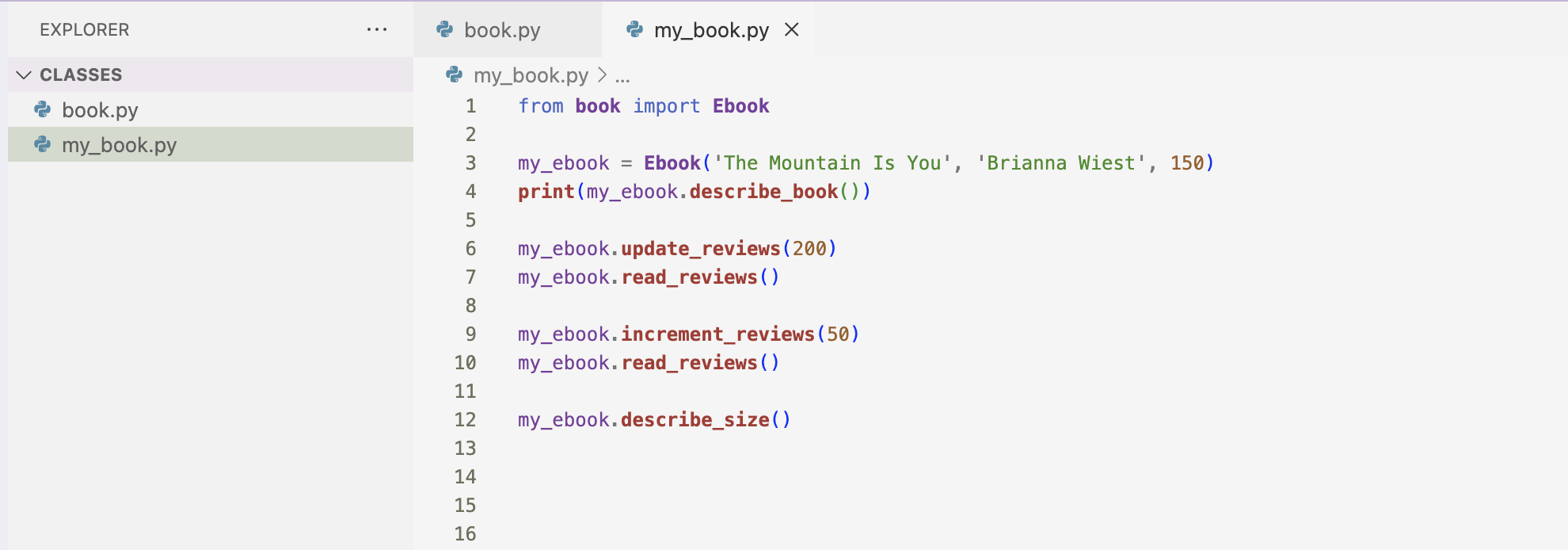

I imported my Ebook class.

Here is the result from running the my_book.py file.

Here are some additional ways I can import classes. These are similar to what I explored in Chapter 8.

Importing an Entire Module

import bookImporting All Classes from a Module

from book import *Importing a Module into a Module

from book import BookUsing Aliases (importing a class)

from ebook import EBook as EBUsing Aliases (importing a module)

import ebook as ebThat is all for Chapter 9. Moving on to Chapter 10!