Chapter 8 was all about functions. A function is a reusable block of code that performs a specific task. It helps organize your code and makes it more readable and maintainable.

Some key aspects of functions include:

Reusability: Functions can be called multiple times throughout your program, which saves you time and effort from rewriting the same code.

Modularity: Functions break down complex programs into smaller, manageable pieces, making your code easier to understand and maintain.

Parameters and Arguments: Functions can accept inputs, called parameters, which can be used within the function’s code. When you call a function, you provide arguments (values) that correspond to the function’s parameters.

Return Values: Functions can optionally return a value as output. This value can be used in other parts of your program.

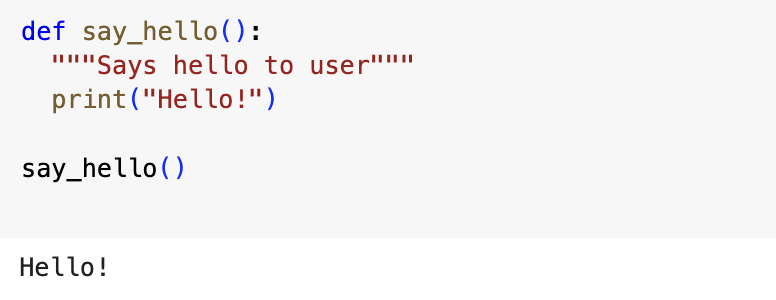

Below is a function named say_hello() that says hello to a user.

The first line includes, def, a keyword that defines the function. This line is known as the function definition which tells Python the name of the function and, if needed, what kind of information the function needs to do its job (this is done inside the parentheses). The parentheses is required even if there is no information needed. The function definition always ends with a colon.

Any indented lines that follow the function definition make up the body of the function. The second line is a docstring, a comment that describes what the function does that is enclosed in triple quotes. The third line is a print statement which in this case is the only actual line of code in the body of this function. The last line is a function call, which is used to tell Python to execute the code inside the function. A function must be called before it’s used.

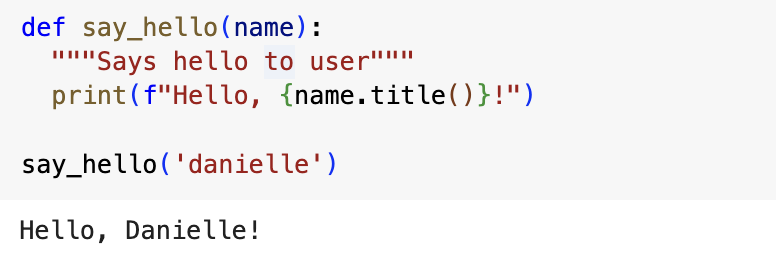

The example below is passing information to the function. I added name inside of the parentheses of the function definition. The variable name is known as a parameter, a piece of information the fuunction eeds to do its job. This allows the function to accept any value of name I give it. The function now expects me to provide a value for name each time its called. When I called say_hello(), I passed it a name, ‘danielle’ inside the parentheses. The function accepted the name I passed it and displayed the message for that name. The value ‘danielle’ in say_hello(‘danielle’) is known as an argument, a piece of information that’s passed from a function call to the function.

Passing Arguments

There are a number of ways to pass arguments to functions.

When a function is called, Python must match each argument in the function call with the parameter in the function definition.

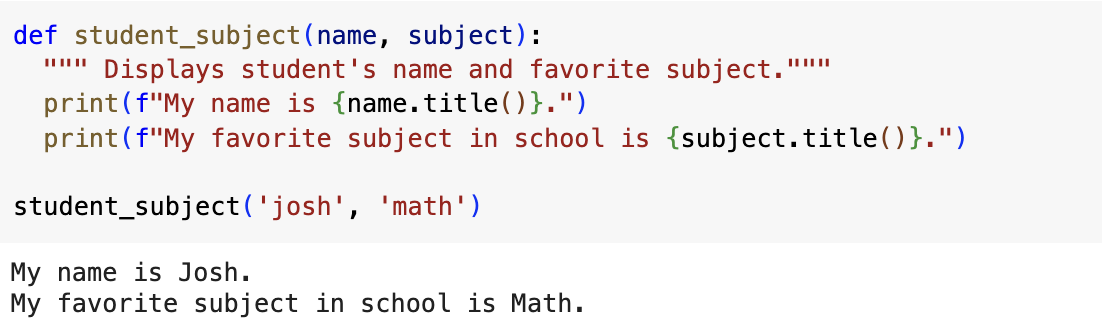

The first way I explored was using positional arguments.

Positional arguments need to be in the same order the parameters were written.

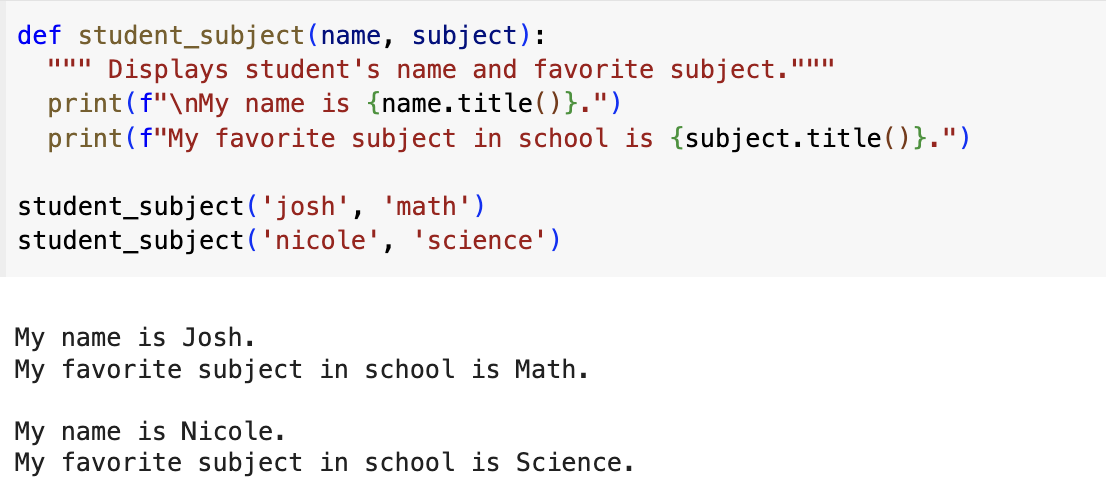

I can call a function as may times as needed, Here I call the student_subject() function twice.

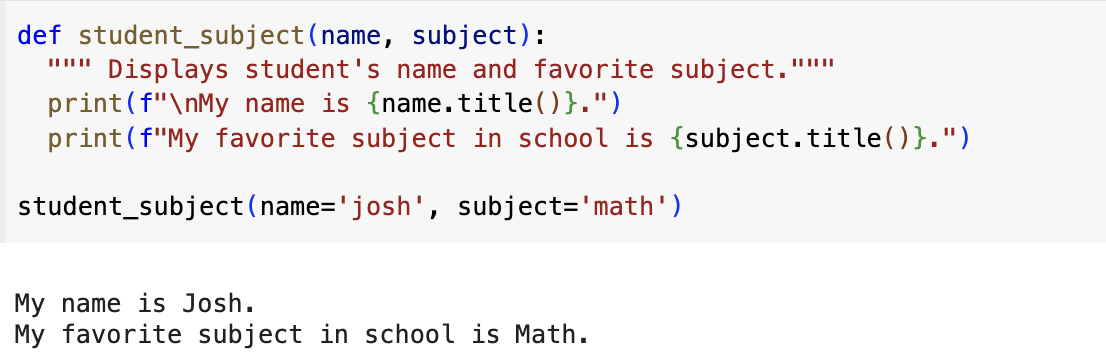

The second way I explored passing arguments is using keyword arguments.

With keyword arguments, I directly associate the name and value within the argument, so when the argument is passed I don’t have to worry about correctly ordering the arguments in the function call, then clarifying the role of each value in the function call.

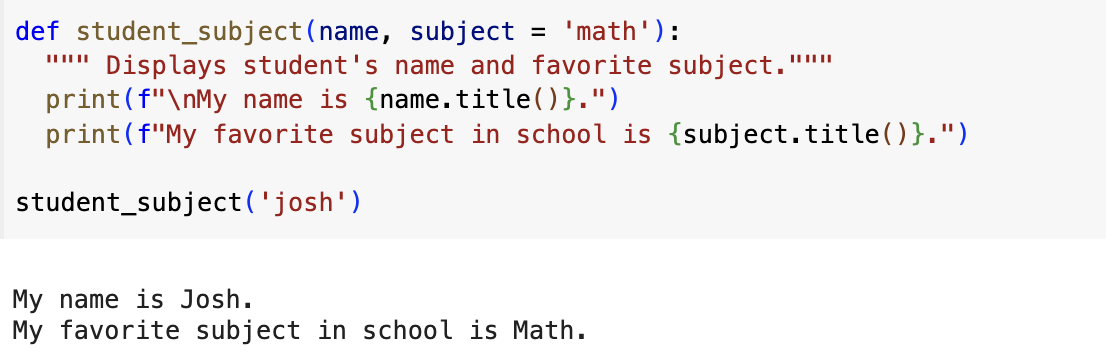

I can also set a default value in the function definition and just provide the student’s name in the function call.

Positional arguments, keyword arguments, and default values can all be used together, so there are often several ways to call a function.

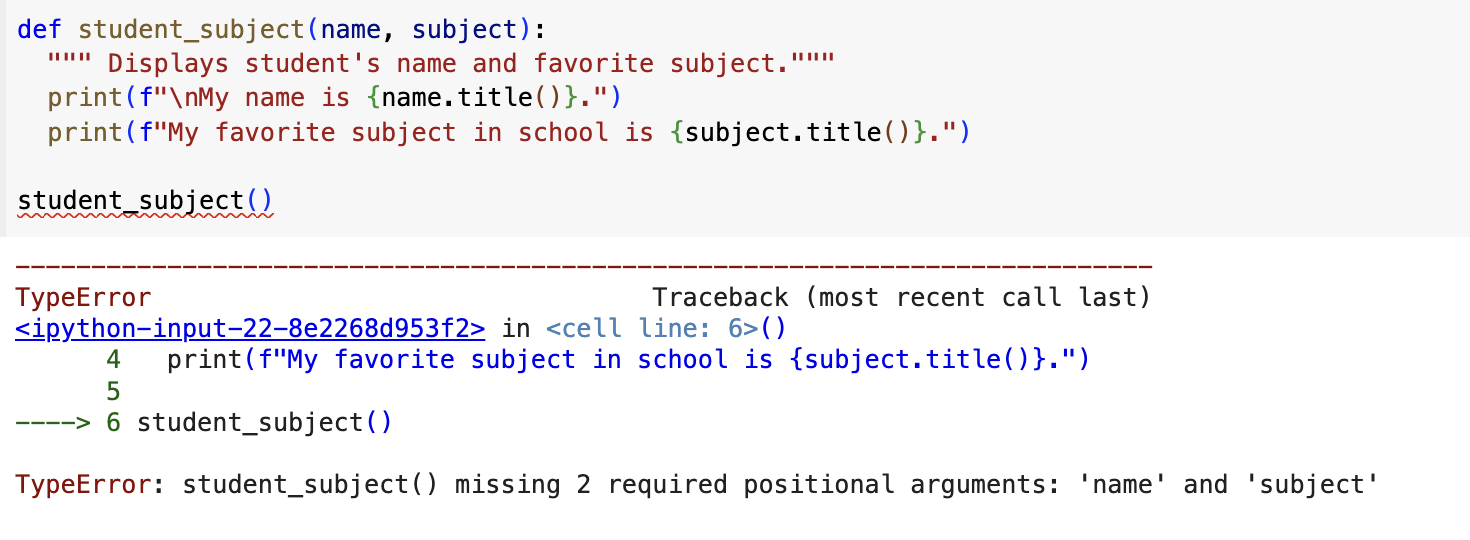

When working with functions, I sometimes would get the error below. This error occurs when the arguments don’t match. Unmatched arguments occur when the function is provided fewer or more arguments than the function needs to do its work.

Return Values

Sometimes functions don’t need to display anything on the screen. Instead, they can crunch data and give you an answer. This answer, called a return value, gets sent back to the place that called the function. Using return values can make your programs run smoother by letting you break down complicated tasks into functions.

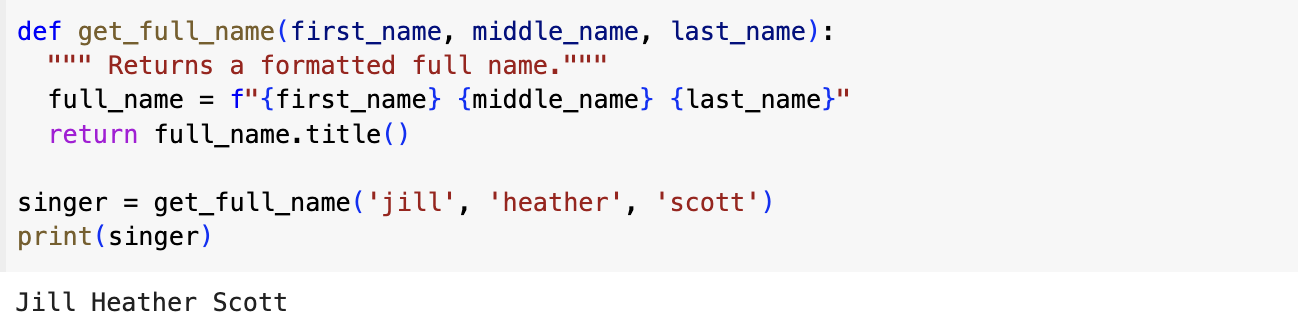

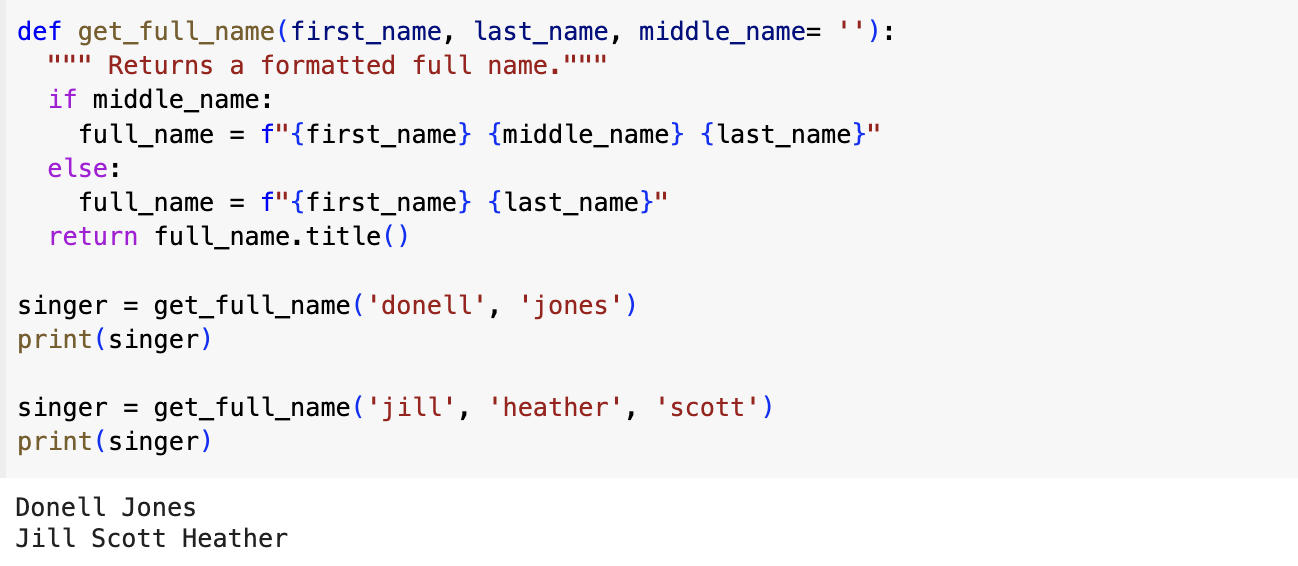

Let’s look at the function below that returns a simple value.

This function takes a first, middle and last name, and returns a full name.

The definition of get_full_name takes three parameters: first_name, middle_name and last_name. The function combines these three names and adds a space between them, and assigns the result to full_name. The value of full_name is converted to title case and returned to the calling line.

When I call a function that returns a value, I need to provide a variable that the return value can be assigned to. In the example, the returned value is assigned to the variable singer. The output shows a formatted full name.

What if a middle name is not given? The code above wouldn’t work if I tried to call it with only a first name and a last name.

The solution to this would be to make the middle name an optional argument, so that when I use the function I can choose to provide a middle name only if I want to. An example of this is shown below.

To make the middle name optional, I gave the middle name argument an empty default value and the argument is ignored unless a middle name is provided. The function worked without a middle name because I set the default value of middle_name to an empty string.

The body of the function is an if-else statement. If the middle name is provided, the if statement evaluates to True and the first, middle, and last names are combined to form a full name. Otherwise, the if statement evalutes to False, the else statement runs and combines only the first and last names to form a full name.

I proceed to call the function twice: once for a singer with only a first and last name and the second time for a singer with first, middle and last names. The formatted names returned to the calling line where they are assigned to singer and printed. When using the middle name, I had to make sure the middle name argument was the last argument passed so Python matched up the positional arguments correctly.

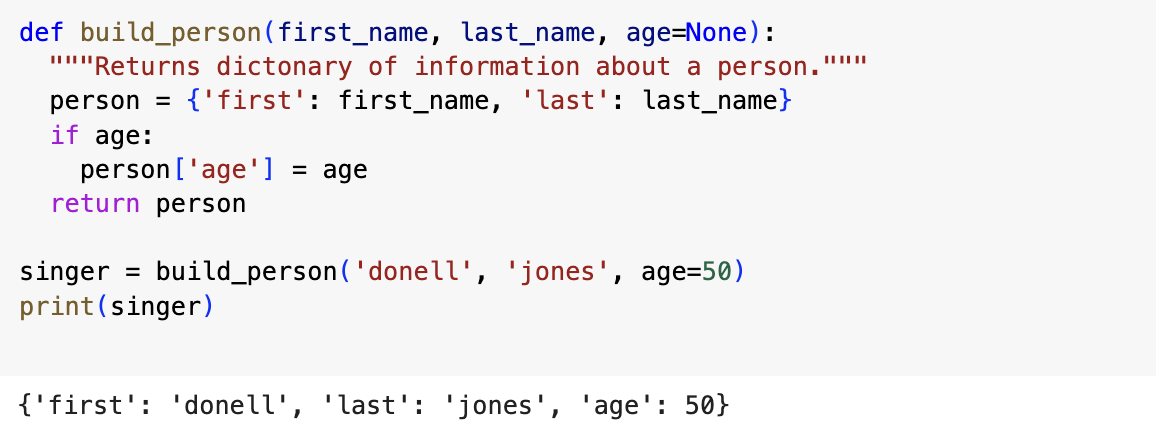

I can use functions with dictionaries and loops.

The first example is using a function with a dictionary. I added the optional parameter age to the function definition and assigned it to the special value None which I thought of as a placeholder. If a function call includes a value for age, that value is stored in the dictionary.

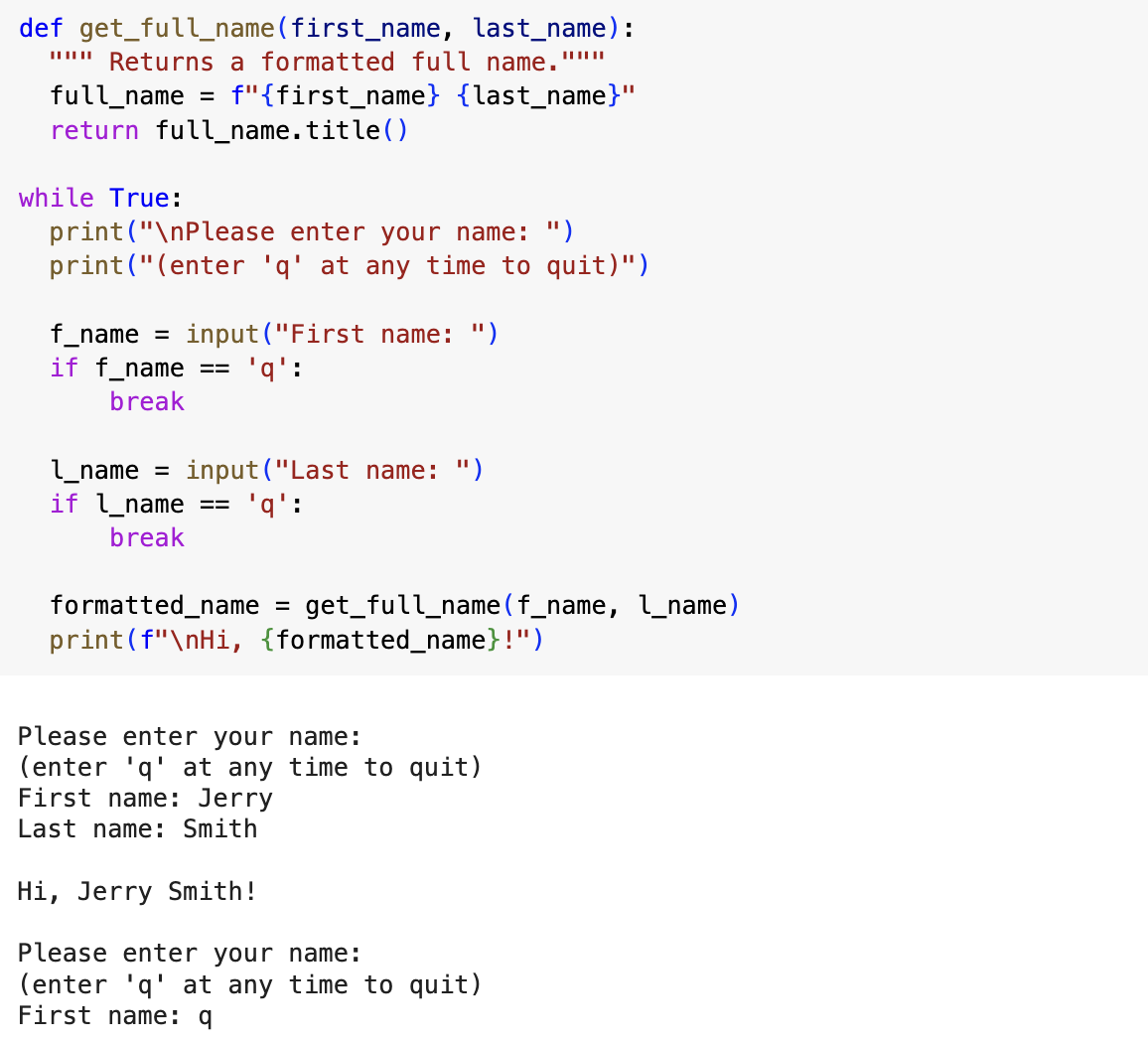

This example is using a function with a while loop. The while loop asks a user for their name and informs them that they can quit the program at any time using ‘q’. I prompt the user for their first name and last name separately. If the user enters their first name and last name, their full name is printed. If the user enters ‘q’ the program, exits the loop.

Passing a List

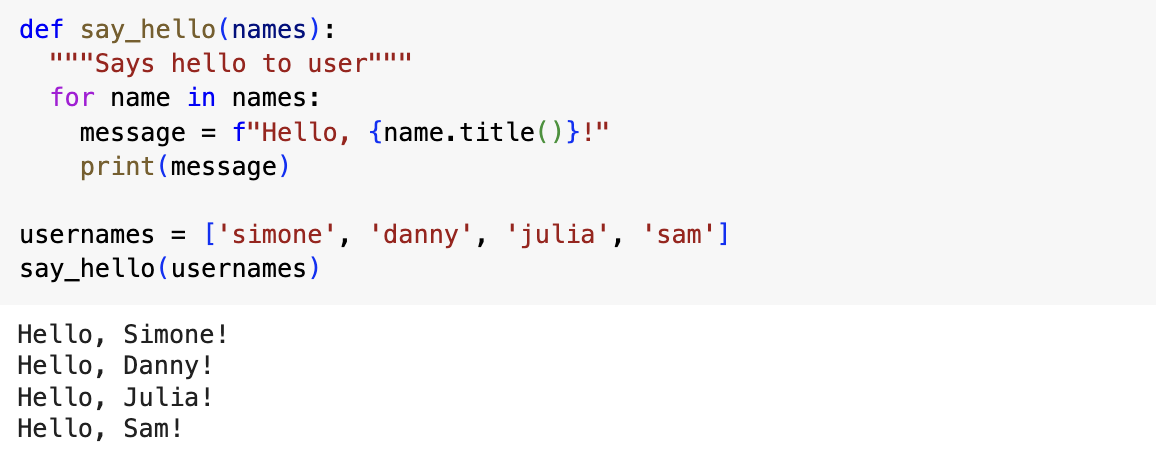

It can be useful to pass a list to a function. When a list is passed to a function, the function gets direct access to the contents of a list.

I have a list of users and to print a greeting for each person. I define the say_hello() function with names as the parameter. The function loops through the list it receives and prints the greeting to each user. I defined a list of users and pass the list usernames to say_hello() in the function call.

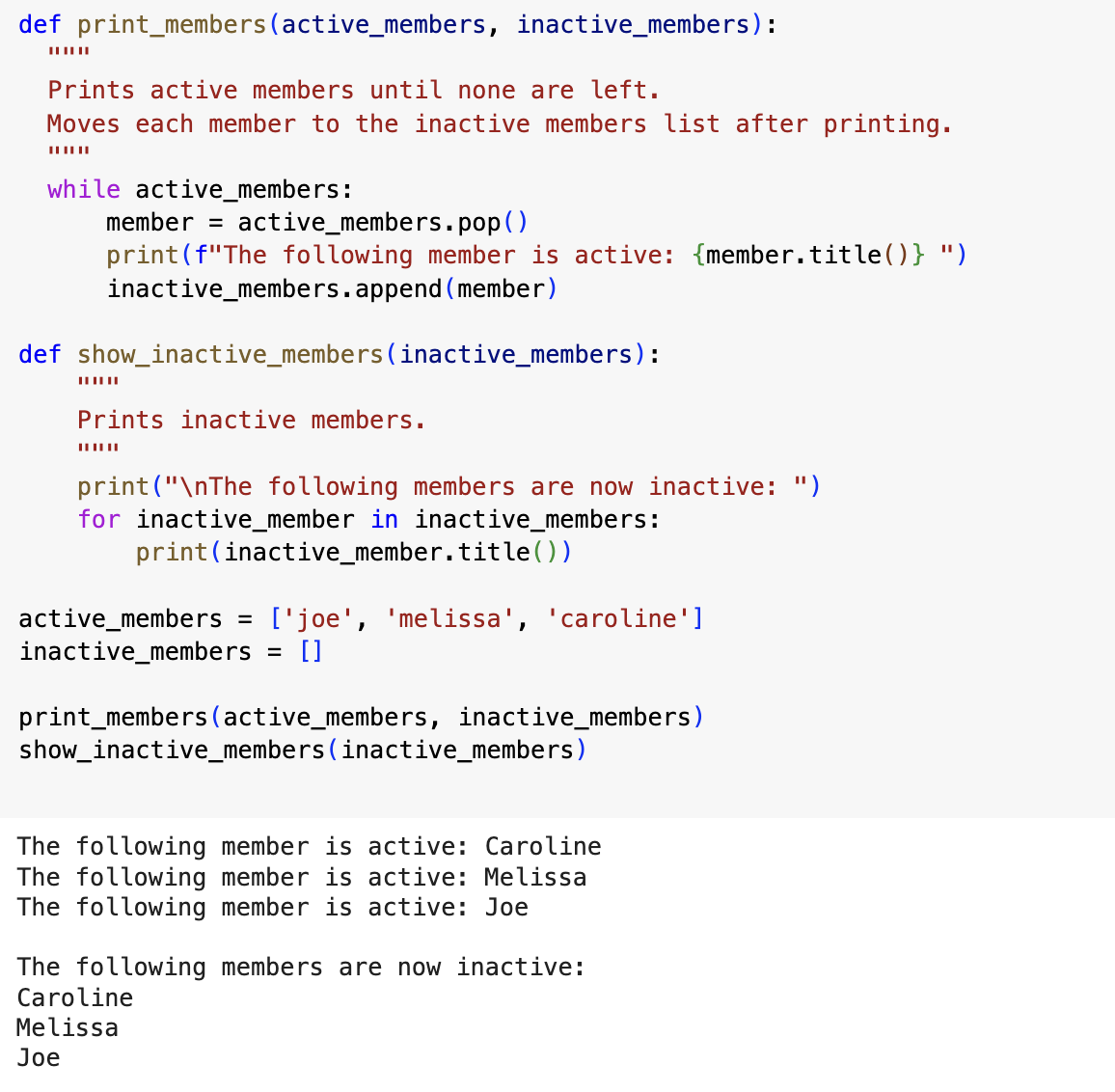

I could use a function to modify a list. The example below is similar to the example I showed in a previous post. In this example, I used two functions. the first function prints the members in the active_members list, empties that list, and moves the members to the inactive_members list. The second function prints the members in the inactive_members list.

Passing an Arbitrary Number of Arguments

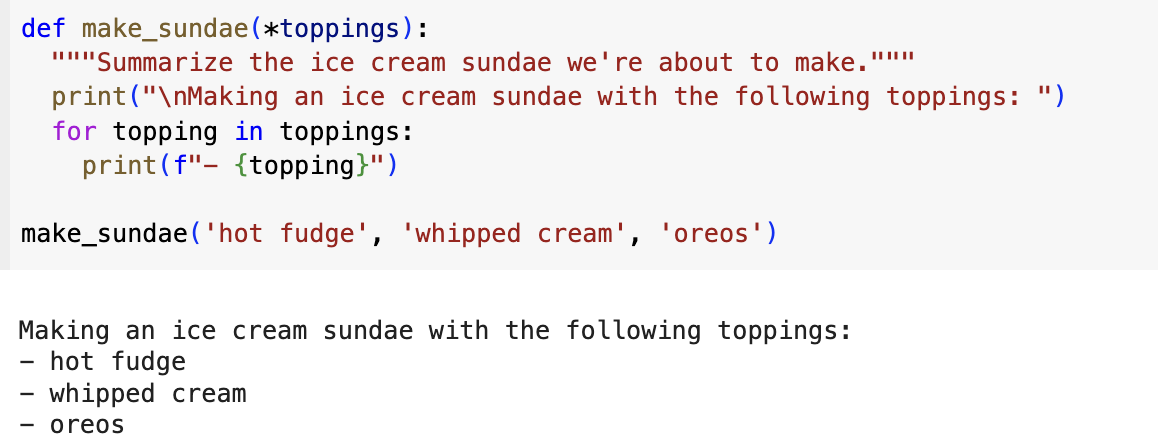

I won’t always know ahead of time how many arguments a function needs to accept. Python allows a function to collect an arbitrary number of arguments from the calling statement.

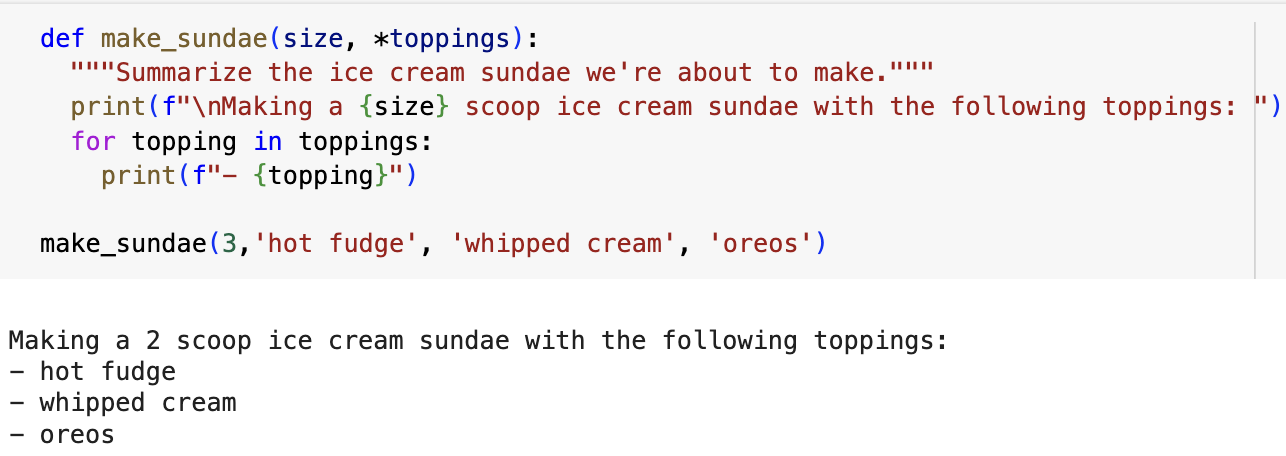

I can mix positional and arbitrary arguments as shown below.

In the function definition, I added the parameter size. All other values that come after are stored in the tuple toppings. The function calls include an augment for size first followed by as many toppings as needed.

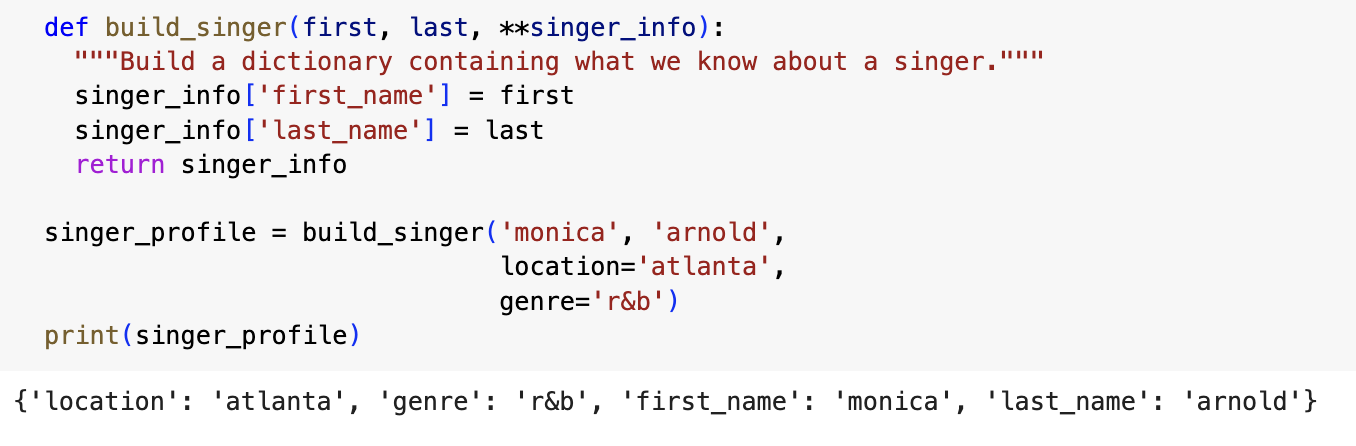

Using arbitrary keyword arguments are another option. Here the function definition expects a first and last name, and then allows the user to pass in as many name-value pairs as needed. The double asterisk before the parameter **singer_info causes Python to create a dictionary called singer_info containing all the extra name-value pairs the function receives. I can access the key-values pairs in singer_info like I would any other dictionary.

I added the first and last names to the dictionary and return the singer_info dictionary to the function call line. I called build_singer to add the first and last name, and two key-value pairs: location and genre. I assigned this to singer_profile and printed singer_profile.

Modules

For the final section of this post, I’ll discuss modules.

I can store my functions in a separate file called a module and then import that module into the main program. An import statement tells Python to make the code in a module available in the currently running file.

I first created the directory sundae and created two files: sundae.py and making_sundae.py.

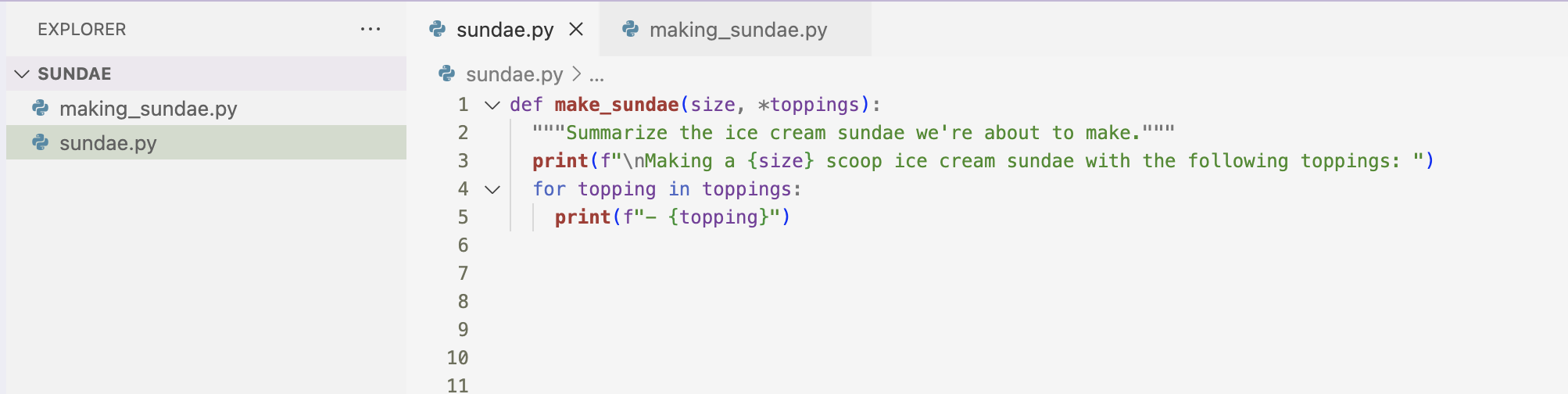

Here is the sundae.py file that includes the function make_sundae().

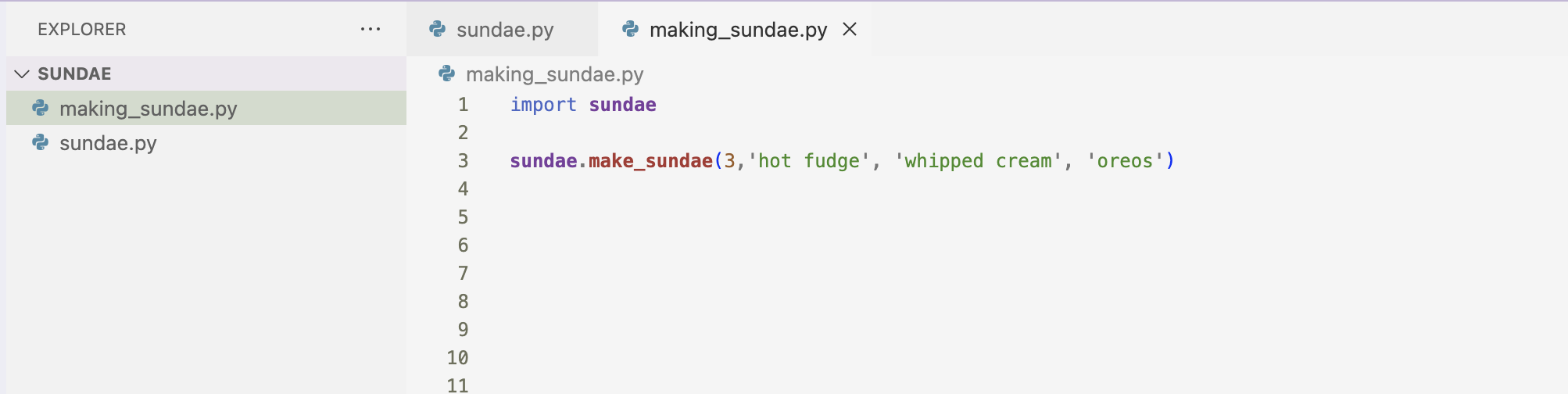

Here is the making_sundae.py file where I imported sundae using the line import sundae. This line tells Python to open the file sundae.py and copy all the functions from it into this program. To call a function from an imported module, I entered the name of the module I imported, sundae, followed by the name of the function, make_sundae(), separated by a dot.

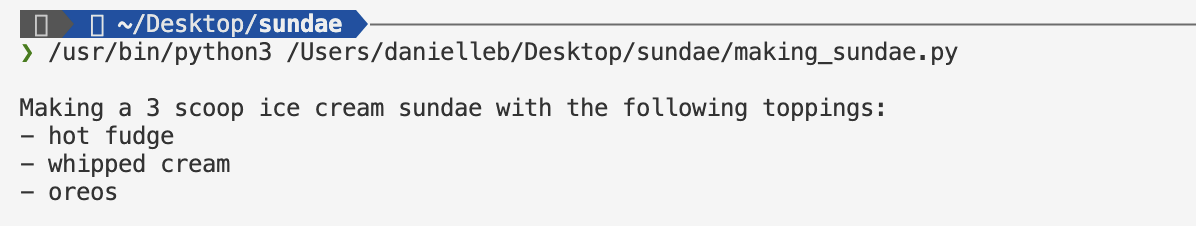

This prints out the same output as the original program.

There are several ways to import the function from the module.

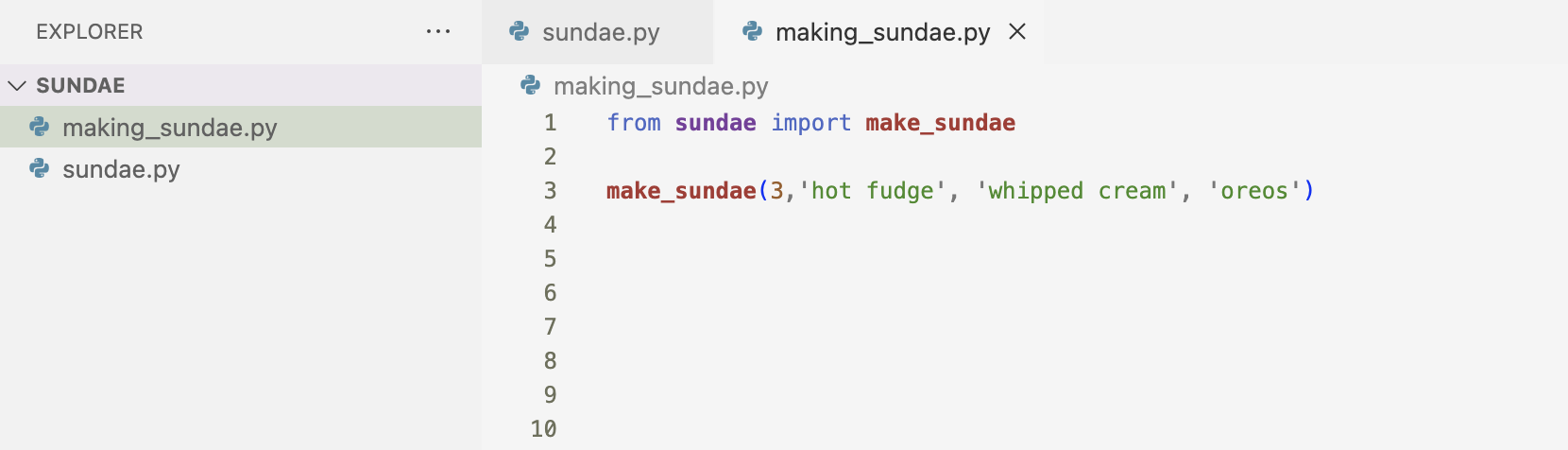

I can import the specific function make_sundae().

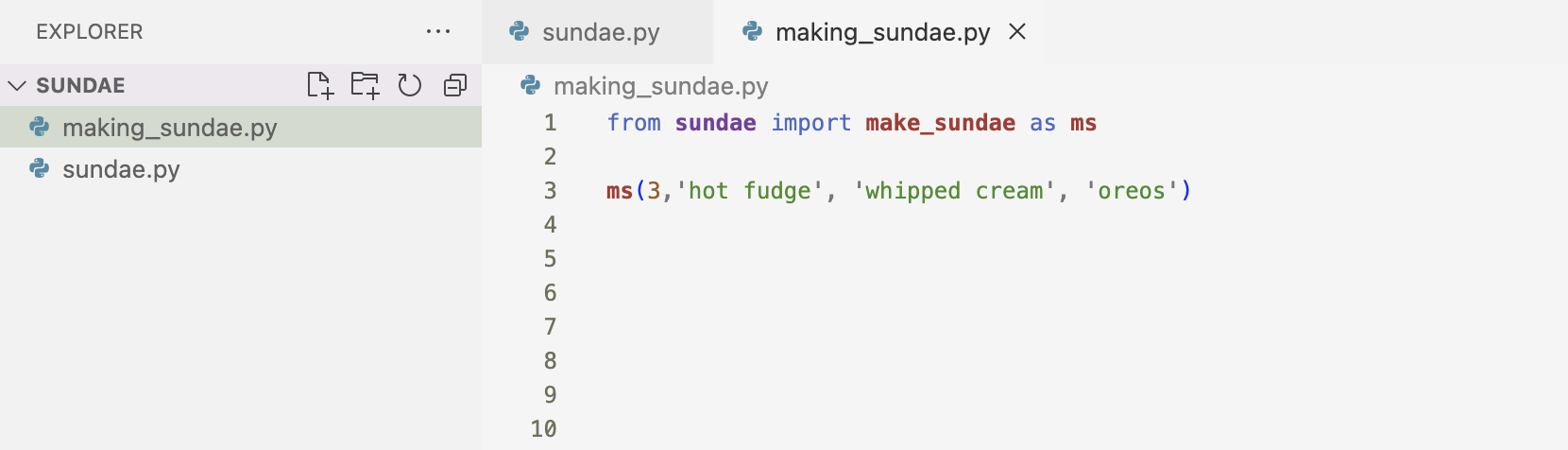

I can give the function an alias.

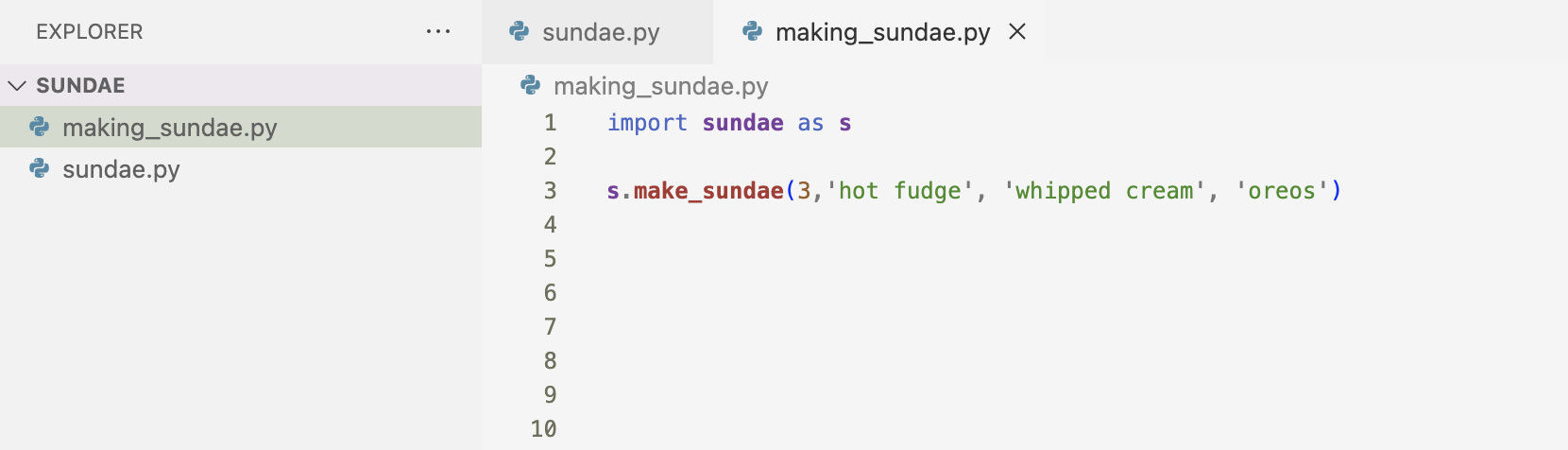

I can give the module an alias.

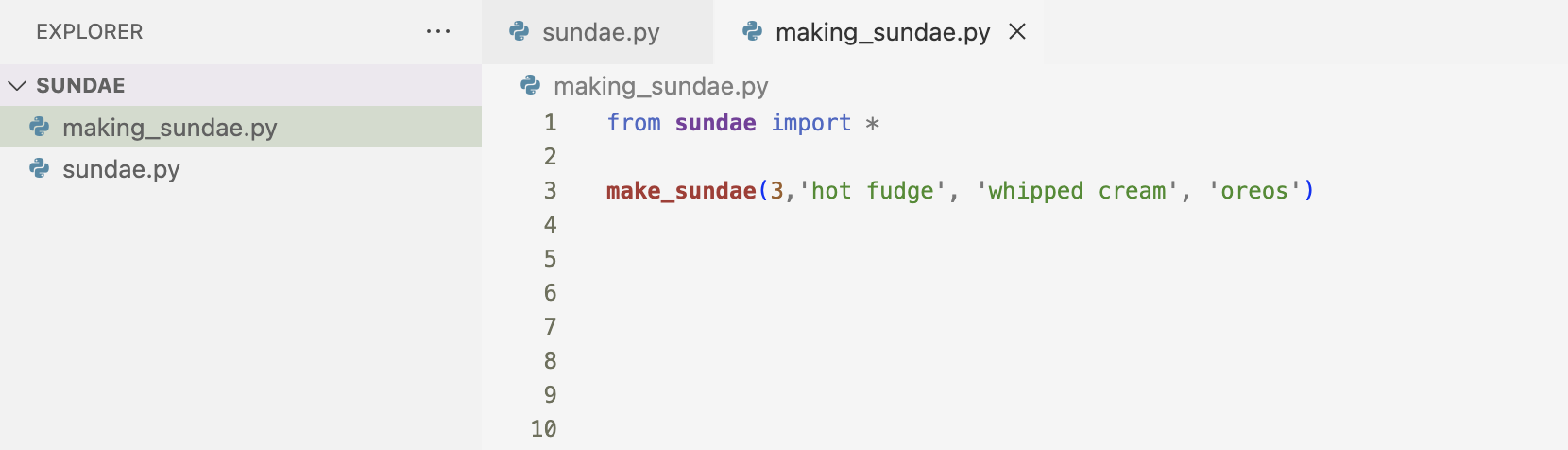

I can choose to import all functions in the module. In this case, there is only one function but I thought this would still be useful.

All of these methods produce the exact same output that I originally had.

That’s all for chapter 8! On to chapter 9!